Enys Men (2023)

Directed & Written by Mark Jenkin

Starring Mary Woodvine, Edward Rowe, Flo Crowe, John Woodvine, Joe Gray, & Loveday Twomlow.

Horror

★★★1/2 (out of ★★★★★)

Mark Jenkin’s Enys Men is a slow-burning, surreal story about a Volunteer (Mary Woodvine) working on a remote, uninhabited island off the Cornish coast during 1973. The Volunteer sees a rare flower growing on the island, so she records temperatures and makes note of any new growths on the flowers. After a while, lichen grows from the flowers. The Volunteer likewise notices that her body itself is sprouting lichen, too. And all around her there are ghostly sounds, even ghostly physical presences, coming from the land. The Volunteer tries to figure out what’s going on, as time and space shift around her.

Although Enys Men could’ve worked better it remains an impressive rumination on the power, the presence, and the longevity of grief on not only an individual level but a community level, too. The Volunteer’s surreal experience as she watches over new flowers growing on Enys Men whisks her into the existential workings of grief, as she experiences her own memories of past trauma while simultaneously experiencing the memories of trauma that exist within the land itself. What the Volunteer experiences is a link between the human body and the land. Jenkin’s film explores how bodies and land retain the traumas of the past, but they do not have to be a living monument of our grief. The film suggests, in the end, that we are capable of remembering the past without having to drown in it.

“The flowers have gone.”

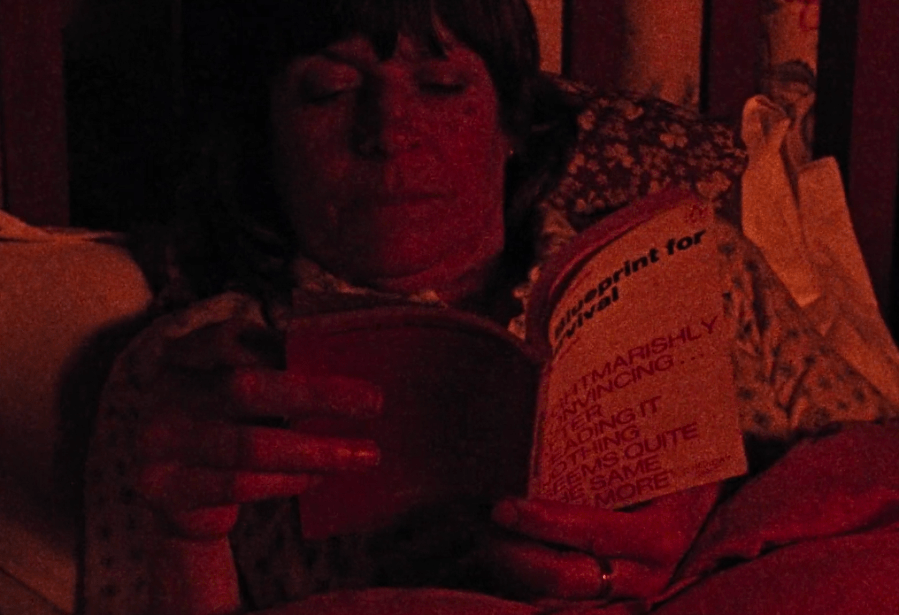

A significant theme in Enys Men is the tension between industrialisation and the natural world, which makes locations featuring old mines in Cornwall appearing throughout the film an important piece of Jenkin’s surreal puzzle. One of the most glaring images pertaining to industrialisation v. the natural world is the book A Blueprint for Survival (1972) read by the Volunteer. A Blueprint for Survival was written by Edward Goldsmith and Robert Allen. It was an environmentalist text that, among other things, recommended living in small, decentralised, largely de-industrialised communities. Goldsmith and Allen hoped to prevent “the breakdown of society and the irreversible disruption of the life–support systems on this planet.” A Blueprint for Survival is also contrasted later with a shot of the Volunteer reading it, then a shot of the preacher the Volunteer sees in a vision of the past holding a big, ancient-looking Bible, juxtaposing the ideologies of dusty old men preaching for industry and a woman like the Volunteer trying to heal and repair the land.

A significant theme in Enys Men is the tension between industrialisation and the natural world, which makes locations featuring old mines in Cornwall appearing throughout the film an important piece of Jenkin’s surreal puzzle. One of the most glaring images pertaining to industrialisation v. the natural world is the book A Blueprint for Survival (1972) read by the Volunteer. A Blueprint for Survival was written by Edward Goldsmith and Robert Allen. It was an environmentalist text that, among other things, recommended living in small, decentralised, largely de-industrialised communities. Goldsmith and Allen hoped to prevent “the breakdown of society and the irreversible disruption of the life–support systems on this planet.” A Blueprint for Survival is also contrasted later with a shot of the Volunteer reading it, then a shot of the preacher the Volunteer sees in a vision of the past holding a big, ancient-looking Bible, juxtaposing the ideologies of dusty old men preaching for industry and a woman like the Volunteer trying to heal and repair the land.

It’s also interesting that Enys Men is set in 1973, the year the United Kingdom joined the EEC (European Economic Community), which was later absorbed into the European Union, and now 50 years later, the U.K. is no longer part of the EU whatsoever. Enys Men‘s 50-year gap, from a time when the U.K. was entering into the EU and a time after the U.K has left it, is a Gothic whisper from out of the past that’s critical of where things continue to head. The film’s setting in 1973, along with its environmental themes, as well as the reality of the U.K. entering what became the European Union in that same year, speaks directly to the state of the environment prior to EU environmental laws and after them. In the real world, Cornish land was traumatised by the Industrial Revolution, and in 1973 when the Volunteer comes along, and the U.K. was entering into the ECC, people and communities were attempting to help the land heal. Now, as Enys Men is released in 2023, the United Kingdom’s various lands remain in a vulnerable state once more, ready to be traumatised all over again.

Perhaps the most glaring point in Jenkin’s film is that the land bears trauma just like people do, which is why Enys Men draws parallels between Cornish mining history inflicting trauma on the natural world, as well as people, and the Volunteer’s personal, bodily traumas. We see the earth’s wounds in the film, as the Volunteer quietly laments the state of the land, looking into the open, gaping wounds of the world: the old mining pits. Then there are all the industrial relics, from the old mines themselves to mining equipment left buried or embedded into the land. We can compare the pieces of metal and other debris embedded into the island’s dirt with the Volunteer’s lichen-covered wound. Jenkin seems to parallel the Earth—perhaps Mother Earth, or Mother Nature—with the Volunteer’s body, which is further shown through how the Volunteer seems to be revisiting not only her own past but also the past of the land on which she finds herself.

One of the major elements in Enys Men is the many uncanny Gothic experiences of the Volunteer. She continually sees her younger self on the island, including a traumatic moment that leaves her with the scar we repeatedly see; she sees her own double hauling the drowned boatman from the water; she witnesses herself dancing with the boatman; and she experiences plenty other surreal, hallucinatory moments, many of which are assumedly from her personal past. The past is generally everywhere throughout Enys Men. We see it in the land, and also in the little home where the Volunteer spends her time on the island. One particularly significant image is a piece of the Governek, a ship with a tragic fate for all involved, sitting on the mantle of the house; at one point, it actually looks wet, running with water, as if just recently pulled from the waves and the wreckage, not a century before. Jenkin further uses history in an uncanny, meta-fictional sense, in that Enys Men is not a real island but its fictional history mirrors the history of other real mines in Cornwall. We see bits and pieces about the Govenek, as well as other slivers of history from 1897, which feels eerily similar to actual history from Wheal Owles: in January of 1893, twenty miners (nineteen men, one boy) lost their lives after a flood from the neighbouring Wheal Drea rushed into Wheal Owles. What’s so interesting is that Wheal Owles is one of the actual locations used in Enys Men—an evocation of history in the plot and the landscape itself.

Men appear in all the visible tragedies of the film, standing in stark contrast with the near-invisible bal maidens whose work and sacrifices are not commemorated. Even the miners way beneath the earth are seen, but the bal maidens appear like an afterthought, ghostly figures upon the land rather than workers like the men. The bal maidens appear in the last act of the film, surrounding the Volunteer. A bal maiden (bal = Cornish for mine, maiden = English for young or unmarried woman) was a woman doing manual labour in the mining industries of Cornwall and western Devon throughout the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. Bal maidens didn’t work in the mines, they worked on the surface. They often processed ore sent up from underground by the male miners. They typically began working around age 10 and if they married they left work, but if they did not marry they continued to work in mining into their senior years. Depending on age and health, bal maidens post-Industrial Revolution had various jobs from picking and sorting the ore, to break the ore, to carrying and crushing ore, and so on. In history, bal maidens are largely ignored. It’s often considered that men did the mining, and so all those achievements of mining are attributed to men and masculinity, just as it is with many other industries; progress throughout history has been considered as inherently a masculine process. Similarly in Enys Men, the bal maidens only turn up later in the film, and they’re not focused on much until the very end when the Volunteer tries to turn the tides of history.

Men appear in all the visible tragedies of the film, standing in stark contrast with the near-invisible bal maidens whose work and sacrifices are not commemorated. Even the miners way beneath the earth are seen, but the bal maidens appear like an afterthought, ghostly figures upon the land rather than workers like the men. The bal maidens appear in the last act of the film, surrounding the Volunteer. A bal maiden (bal = Cornish for mine, maiden = English for young or unmarried woman) was a woman doing manual labour in the mining industries of Cornwall and western Devon throughout the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. Bal maidens didn’t work in the mines, they worked on the surface. They often processed ore sent up from underground by the male miners. They typically began working around age 10 and if they married they left work, but if they did not marry they continued to work in mining into their senior years. Depending on age and health, bal maidens post-Industrial Revolution had various jobs from picking and sorting the ore, to break the ore, to carrying and crushing ore, and so on. In history, bal maidens are largely ignored. It’s often considered that men did the mining, and so all those achievements of mining are attributed to men and masculinity, just as it is with many other industries; progress throughout history has been considered as inherently a masculine process. Similarly in Enys Men, the bal maidens only turn up later in the film, and they’re not focused on much until the very end when the Volunteer tries to turn the tides of history.

In Enys Men, the body is the land, the land is the body. The Volunteer cuts a flower late in the film, yet earlier we heard mention that the flowers shouldn’t be cut. It’s a man who tells the Volunteer this is so, even if she’s the one there for purposes of science. It’s all about where the Volunteer places the flower when she cuts it. The old memories of the island prioritise the contributions and sacrifices of men, and they fester in the land, leeching into the bodies of those who walk it, similar to how societies across the world have prioritised the industrial world above the needs of Mother Nature. In the end, the Volunteer puts the flower at the base of a large rock—one that’s phallic in shape, dripping with white streaks—not far from the house which has grown over with vegetation, becoming part of the land. The Volunteer hopes that maybe this will bring new, different life to the area. And so, we can cut out the memory and, like the flower, put it in a glass of water to keep someplace to remember it, or we can plant it somewhere new in order to let it carry on new life somewhere new. We do not have to inundate our lives with the traumatic memories of our past, to flood our present with the depressing pieces of the past. If we allow those memories, those wounds, to fester, and once the soul (of the body or the land) is infected, it poisons everything else. But it’s always good for a memory to leave a scar, for better or worse, because we should never, ever forget. This is what I took from Enys Men. The benefit of such a unique, surreal film is that each viewer can determine their own interpretation, not fettered to a single, definable meaning handed down by the director; even if Jenkin has a single meaning for everything as the artist, the audience, especially when viewing something so surreal, is still able to locate their own reading of the film however they manage to cobble together the pieces of his puzzle.

Pingback: Reviews: Enys Men (2023) – Online Film Critics Society