Witte Wieven (2024)

Directed by Didier Konings

Screenplay by Marc S. Nollkaemper

Starring Anneke Sluiters, Len Leo Vincent, & Reinout Bussemaker.

Horror / Mystery

★★★★1/2 (out of ★★★★★)

DISCLAIMER:

The following essay

contains SPOILERS!

Look away, or forever be spoilt.

Witte Wieven (retitled as the much more boring Heresy for English-speaking audiences) is a new film set in the medieval period that would fit well on a triple feature at the cinema with Hagazussa and the recent shocker The Devil’s Bath. Didier Konings’s film takes place in a small Dutch village where poor Frieda (Anneke Sluiters) is struggling to fit into the place she’s supposed to fit amongst a patriarchal society. She hasn’t yet gotten pregnant despite the fact she and her husband Hikko (Len Leo Vincent) do everything possible to try making a child. She falls back constantly on her faith and their local holy man Bartholomeus (Reinout Bussemaker). But when she returns from the woods one night, after surviving the darkness of the forest and the darkness of man alike, she’s accused of witchcraft. It seems ridiculous at first to most in the village except her accuser. That is, until Frieda’s luck stats to change, which only brings about terrifying consequences for everybody.

Witte Wieven is a harrowing tale of the power religion and patriarchy hold over individuals and entire communities. Frieda is one woman in a long line of women brutalised by the expectations put upon them by their faith and betrayed by the Christian men who were meant to cherish them. At every step, she’s blamed, abused, and treated like a vessel for whatever men want. She’s able to finally escape it all through the power of women before her, the eponymous witte wieven. Konings’s film is a testament to the power of women relying on women, whether in this life or beyond the supernatural veil. The misogyny Frieda experiences is patriarchy at its most vicious, as she becomes the scapegoat of her own marriage when it’s obvious she and Hikko can’t conceive a child. She’s the one who has to piss into a clay pot and bury it to see if it becomes infested with worms, which means she’s barren; a medieval “fertility test” no doubt conjured up by a man. But it’s when she dares to even suggest that Hikko might need to take a kind of test of his own that the misogyny burns bright. Hikko all but launches across the table at his wife: “Never imply that it‘s my problem, Frieda. This is on you, only you, not me.” There’s never any pressure put upon the man, only the woman. It’s almost analogous to the way a man called Gelo (Leon van Waas) is punished and let out again to just go right back to his lecherous activities, blaming the young woman he attacked because he claims that “in lust” it’s only one person to blame. The suggestion is that Gelo has attacked and raped the young woman, but he, in typical patriarchal, misogynistic fashion, puts partial blame on her for somehow enticing his violent lust. No matter what a woman does in this little Dutch community, she’s doomed. Not even prayer is safe from misogyny, as Frieda begins praying in front of the congregation and she’s corrected: “A prayer never begins with the woman, Frieda.”

The misogyny Frieda experiences is patriarchy at its most vicious, as she becomes the scapegoat of her own marriage when it’s obvious she and Hikko can’t conceive a child. She’s the one who has to piss into a clay pot and bury it to see if it becomes infested with worms, which means she’s barren; a medieval “fertility test” no doubt conjured up by a man. But it’s when she dares to even suggest that Hikko might need to take a kind of test of his own that the misogyny burns bright. Hikko all but launches across the table at his wife: “Never imply that it‘s my problem, Frieda. This is on you, only you, not me.” There’s never any pressure put upon the man, only the woman. It’s almost analogous to the way a man called Gelo (Leon van Waas) is punished and let out again to just go right back to his lecherous activities, blaming the young woman he attacked because he claims that “in lust” it’s only one person to blame. The suggestion is that Gelo has attacked and raped the young woman, but he, in typical patriarchal, misogynistic fashion, puts partial blame on her for somehow enticing his violent lust. No matter what a woman does in this little Dutch community, she’s doomed. Not even prayer is safe from misogyny, as Frieda begins praying in front of the congregation and she’s corrected: “A prayer never begins with the woman, Frieda.”

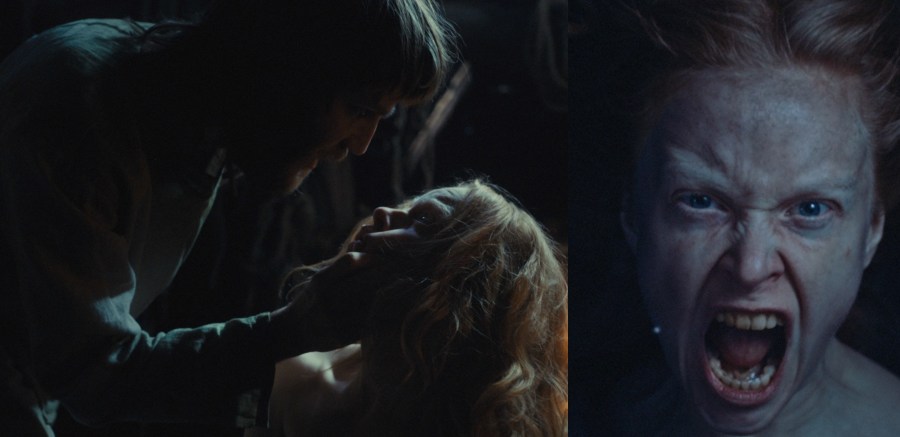

Witte Wieven portrays the violent consequences when religion and patriarchy intertwine at the family/marriage level when Frieda’s advised to rely on what her faith taught her, which leads her to mortification of the flesh by way of self-flagellation, a common practice during the Middle Ages. As Frieda whips herself across the back with a length of rope, she’s watched by her husband, and when he determines she isn’t suffering enough, “like Christ on the cross,” he takes the rope himself and starts to viciously beat her. She flinches too much so he scolds her: “Be quiet and suffer as you should.” She convinces him to stop, but the damage is done, and even he realises how far his misogynistic anger at his wife has gone. When she flees her house, she gets no help, except from the young woman Gelo attacked, Sasha, but even Sasha’s father stops her; he apologises and says they feel bad, yet closes their door to Frieda. The violence of patriarchy in Frieda’s medieval community is an accepted part of everyday life and, obviously, their faith. As Frieda’s dissatisfaction with her existence under the patriarchal thumb grows, she starts having clearer and clearer dreams/visions of a white-haired woman, occasionally letting loose a primal scream. The white-haired woman, whom we realise is part of a larger group of white-haired women, is one of the witte wieven from the film’s title. The witte wieven come from Dutch Low Saxon mythology and legends: they’re spirits of wise women, otherwise known as seeresses in Germanic Paganism and other similar religions; they’re women who can foretell the future and perform magick. The witte wieven are unleashed through Frieda’s anger, incapable of envisioning a future without the crushing patriarchy and misogynistic violence of her community and faith. They’re able to restore Frieda’s hope for a different life and future, though through violent means to match the violence done to her and other women. A significant scene comes following Gelo’s disappearance after he’s found impaled gruesomely in several gory pieces through a tree; a consequence of awakening the witte wieven through Frieda. Later, Frieda stumbles into a patch of forest where there are plenty of other skulls with trees stuck through them, presumably men like Gelo who’ve perished over the years due to their violent sins against women. This place in the woods is a shrine to both the power of women’s revenge and the enduring poison of misogyny that lingers in the blood of patriarchal communities and societies.

As Frieda’s dissatisfaction with her existence under the patriarchal thumb grows, she starts having clearer and clearer dreams/visions of a white-haired woman, occasionally letting loose a primal scream. The white-haired woman, whom we realise is part of a larger group of white-haired women, is one of the witte wieven from the film’s title. The witte wieven come from Dutch Low Saxon mythology and legends: they’re spirits of wise women, otherwise known as seeresses in Germanic Paganism and other similar religions; they’re women who can foretell the future and perform magick. The witte wieven are unleashed through Frieda’s anger, incapable of envisioning a future without the crushing patriarchy and misogynistic violence of her community and faith. They’re able to restore Frieda’s hope for a different life and future, though through violent means to match the violence done to her and other women. A significant scene comes following Gelo’s disappearance after he’s found impaled gruesomely in several gory pieces through a tree; a consequence of awakening the witte wieven through Frieda. Later, Frieda stumbles into a patch of forest where there are plenty of other skulls with trees stuck through them, presumably men like Gelo who’ve perished over the years due to their violent sins against women. This place in the woods is a shrine to both the power of women’s revenge and the enduring poison of misogyny that lingers in the blood of patriarchal communities and societies.

A wonderful moment of solidarity between women occurs near the end while the rest of the village is overcome with fear at Frieda’s unleashed power and Sasha chooses to run into the forest to join Frieda’s escape from their community’s patriarchal tyranny. Witte Wieven depicts so much horror in the lives of medieval women, but it’s all about the power women hold collectively to rise up against those horrors. It’s important, too, that Frieda finds solace and retribution in the realm of legends and mythology, rather than faith. She effectively abandons the patriarchal faith, and the men in charge of that faith, that betrayed her with nothing but terror, then, with help of the witte wieven and the power of the feminine, turns that terror back upon her oppressors. In the end, only Frieda and the women of those woods remain in peace, free of the religious shackles that held them back and harmed them; a beautiful end to a torturous tale.