It’s that time of the year again when most film critics come up with a Best of Year-End List and a small number of absolute cunts come up with a Worst of Year-End List. Unlike previous years, I’ve tried to exclude any titles that haven’t yet received distribution, despite there being a number of incredible films at the festivals throughout 2025; those titles can wait for Best of 2026, though. This list features a few titles that might seem like they were from 2024 but didn’t receive American or Canadian releases until 2025.

Hopefully you enjoyed the cinema of 2025 as much as I did. People routinely love to make statements about how film has declined, seemingly year after year after bloody year since at least the mid 1990s. For me, 2025 was a cracking year, full of weird, wild, emotional, exciting, and dark stories. Let me know if any of these titles resonated with you as much as they did with me, and if so, make sure to check out the essays I’ve written on a number of them.

Oh, and Happy New Year!

Maybe we’ll all live to see 2027. One can hope, anyway.

The Ugly Stepsister

Directed & Written by Emilie Blichfeldt

Fairy and folk tales alike have been vessels through which storytellers have talked about social issues for millennia. They’re timeless vessels, too, as the issues many of them deal with have continued to plague us right up to the current day. One of the oldest issues fairy and folk tales have confronted is the eternal struggle of women in a world dominated by men and harmful male ideas. The Ugly Stepsister—an adaptation of Cinderella, more specifically the version known as Ashputtle recorded by the Brothers Grimm—deals with competition between women and the effects of internalised misogyny, both due to patriarchal control. Emilie Blichfeldt tells a folktale in a brutally real fashion to illustrate the physical toll that beauty standards have on female bodies.

Full essay here.

Friendship

Directed & Written by Andrew DeYoung

Friendship is a dark comedy about some men’s inability to grow and change, as well as the depths of male insecurity. Craig desperately wants to connect with another man, but he’s almost entirely incapable of changing his behaviour, except when things have reached the point of no return. Austin, on the surface, is a man not necessarily afraid of change, yet underneath his carefully crafted exterior is a deeply insecure man whose fragile identity is held together by smoke and mirrors. DeYoung’s film is hilarious and wonderfully cringeworthy at times. It’s also an introspective look at men dealing with their own faults, being rejected by other men, and failing to make even the smallest changes to improve their relationships. Friendship would be funnier than it already is if only it wasn’t so insightful as a riotous, intelligent critique of male insecurity, as well as men’s resistance to personal and social growth.

Full essay here.

The Wailing

Directed by Pedro Martín-Calero

Screenplay by Martín-Calero & Isabel Peña

The Wailing‘s visuals are at times enough to make the skin crawl, as the dark figure gradually infiltrates the women’s lives deeper. The story, while enough on the surface, can be taken as a metaphor of battling against mental illness while those around you are incapable of seeing the things you see. It’s a haunting film that warns of the dangers in not listening to those struggling with mental illness. Andrea and Marie struggle because, for the most part, their fears of the shadowy man are ignored and dismissed. The Wailing examines the toll it can take to confront a deep darkness by yourself. Pedro Martín-Calero’s film is a supremely dark story that suggests invisible forces, whether supernatural or psychological, can only be fought when people open their eyes and minds to things they don’t initially understand.

Full essay here.

Frewaka

Directed & Written by Aislinn Clarke

The word “Fréwaka” is a phonetic spelling of the Irish word “fréamhach,” translating to “roots” in English, and Clarke’s film is certainly about digging down to the roots of ourselves, our histories, and our greatest fears. Frewaka isn’t only about Shoo, nor Peig, either; it’s about generational trauma that remains present in so many Irish lives. What Shoo and Peig come to confront together, once their shared roots come to light, is the darkness in their own lives and the darkness that has loomed over the Irish for centuries. It’s all about the past. As Faulkner famously wrote in Requiem for a Nun, “The past is never dead, it‘s not even past“; it is always with us, threatening to eat us alive. Frewaka is a chilling reminder that the past clings to body and soul; there’s no outrunning an extra organ.

Full essay here.

Sinners

Directed & Written by Ryan Coogler

Vampires in fiction have traditionally been marked as Other, so the way Ryan Coogler chooses to tell a story in Sinners about various oppressed people, from Black Americans to the Choctaw to the Irish, is enough to make his vampire film, Sinners, incredibly interesting. Sinners is overall a fantastic, expansive vampire story, too. Coogler touches on compelling pieces of history throughout the film that are crucial to see incorporated into fiction since America’s currently living through an era of fascism in which Black history, and any other inconvenient anti-colonial history, has been pushed to back of the nation’s dusty, repressive bookshelf. Sinners is a vital work of American art for this very moment in time.

The Visitor

Directed by Bruce LaBruce

Screenplay by LaBruce, Alex Babboni, & Victor Fraga

Some will watch The Visitor and be appalled by its brazen pornographic sequences. Others will watch and feel that LaBruce’s film gets lost in its own subversiveness. Yet still, more will watch The Visitor and see a masterful, angry, erotic film about a visitor from outside a culture revealing all the dirtiest crevasses of that culture’s mind. LaBruce’s The Visitor is a timely piece of cinema that wants to shake up the white, hetero-patriarchal order of Western societies and get you off in the process, as long as that post-nut clarity pushes you to take the revolution from the bedroom into the streets. In a time when so many people lament what they believe is the politicising of identity, whether sexual, gender, or otherwise, LaBruce sees the inherent politics of various identities, and leans into the transformational power of non-normative identity within a constrictive society like the one white British nationalists envision for their nation. The Visitor is a powerful, erotic film that enthusiastically pushes back against Britain’s dominant white hetero-patriarchal culture, urging the viewer to look at the very idea of national culture from a different perspective, even if that perspective is face down, ass up.

Full essay here.

Weapons

Directed & Written by Zach Cregger

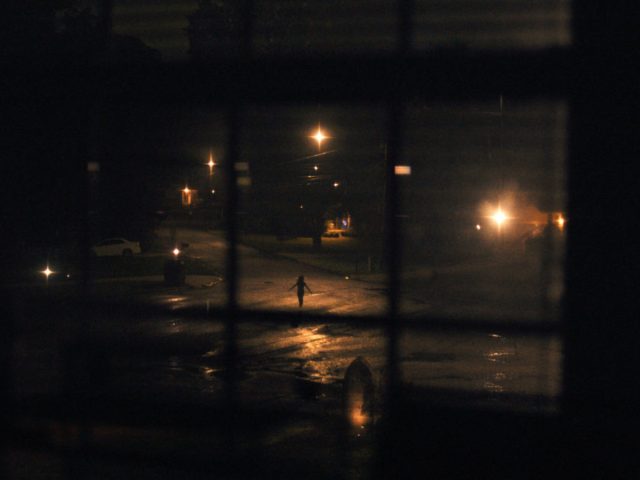

Zach Cregger’s Barbarian was a fantastic, brutal hammer that bludgeoned the viewer, and Weapons is a slow, jagged knife between the ribs into the heart. Weapons does a masterful job of connecting various perspectives of different people in a small town where, one night, a bunch of children walk out of their homes, run into the dark, and seemingly vanish without a trace. What starts as potentially a crime-mystery story evolves into a haunting horror about hypnotising forces beyond our control that seek to manipulate the most vulnerable amongst us. Weapons is an intriguing use of witchcraft horror due to Aunt Gladys (Amy Madigan) and her methods. Cregger’s film also contains a deeper political and social allegory about who’s really manipulating America’s children; it’s not the young progressive teachers, neither is it the gay principal, nor is it the homeless addict, it’s a woman who comes disguised as family, as someone familiar, only to unleash hell on the community around her.

Orwell: 2+2=5

Directed & Written by Raoul Peck

Similar to Adam Curtis, Raoul Peck’s fascinating and sprawling documentaries feel inspired by John Dos Passos’s U.S.A. trilogy in how they pull together so much material over a lengthy span of history, and Orwell: 2+2=5 does this especially well considering the material from a number of countries and cultures it gathers together. Peck’s latest documentary uses George Orwell’s 1984, including Damian Lewis as the voice of Orwell, as a premise to help grapple with an increasing rise of fascism, autocracy, and oligarchy across the globe, touching on the rhetoric, as well as political views and/or policies of people like Donald Trump, Elon Musk, Narendra Modi, Giorgia Meloni, Vladimir Putin, Mark Zuckerberg, Lin Junyue, and more. Peck has an uncanny ability to sew so many threads at once while never losing the audience. Orwell: 2+2=5 diagnoses the symptoms of a sick world diseased with dangerous fabricated narratives, unregulated artificial intelligence, widespread surveillance, and staggering wealth inequality; the only cure is a cocktail of awareness and education, like this documentary.

Die My Love

Directed by Lynne Ramsay

Screenplay by Ramsay, Alice Birch, & Enda Walsh

Die My Love is a mix of beauty, love, madness, pain, and tragedy. The marriage between Grace (Jennifer Lawrence) and Jackson (Robert Pattinson) is a microcosm of many women’s experiences from many different cultures—women who don’t want to sacrifice the romantic love for their spouse just to be sanctioned by society as a ‘proper’ wife and mother. Grace rebels against everyone around her trying to cram her into an ill-fitting box that she simply can’t or won’t fit inside. Jackson’s part in their marriage is also a microcosm of all the men who see their wives as only wives and mothers, not as whole women with desires, goals, and complex needs of their own. Die My Love stings in the way rubbing alcohol does, as it tries to disinfect cultural wounds that many societies have created in the body politic in the way romantic love is so often seen as merely a symptom of marriage, rather than the foundation. In spite of everything, Grace and Jackson are two people who love each other; however, one of the points Ramsay’s film seems to make is that love cannot be in name only, it’s something that requires a bit of elbow grease to maintain, and if it’s allowed to curdle like sour milk, it’ll make everybody sick.

Full essay here.

Good Boy

Directed by Ben Leonberg

Screenplay by Leonberg & Alex Cannon

There’s real magic in Good Boy, as Indy draws the viewer into the film’s reality. Any human being with a real heart can’t possibly resist Indy’s sweet, furry face and soulful eyes. Aside from Indy’s charm, Leonberg works hard to tell a powerful story about not only the loyalty of dogs but about a haunted family that can’t outrun its own history. Good Boy is a horror that contains equal amounts of creeps and heart, combined into a profoundly emotional story about, among other things, how dogs shouldn’t only be viewed as pets, essentially as things we own, but rather as companions, as guides, and, like Indy, as protectors who sometimes keep the monsters at our doors at bay, at least for as long as caninely possible.

Full essay here.

Sirāt

Directed by Oliver Laxe

Screenplay by Laxe & Santiago Fillol

Sirāt is at once very real, very literal, then at the same time deeply metaphorical and poetic: on one hand, Laxe is telling a story about a man dealing with one tragedy who’s faced with escalating tragedies as he tries to deal with the first; on the other hand, Laxe is telling a story about the afterlife and how we cannot escape judgement, nor punishment for the mistakes we’ve made. The Islamic mythology of As-Sirāt, a bridge over which one must pass in order to access Paradise or else fall into the fires of Hell, serves as a metaphor about living through Hell’s fire while still amongst the land of the living—a psychological journey of torment across both a physical and mental desert.

Bleeding

Directed & Written by Andrew Bell

Vampires and compulsive behaviours have long been linked, even prior to Abel Ferrara’s The Addiction (1995), as far back as depictions in Macedonian folklore of vampires driven by arithmomania, a compulsion to count actions/objects. Bell’s screenplay is imbued with a very personal understanding of the opioid crisis in America that has taken so many lives and rendered so many (largely working-class) people into forms of the living dead, walking amongst the shadows seeking their next fix, just as the addicts in Bleeding seek only their next sip of blood. The allegory of vampirism as addiction isn’t new, but Bell uses it in his film to tell an important, haunting, ugly story about the deep darkness of addiction that turns people into horrific versions of themselves and also reveals the monstrosity of those who’d rather stake them in the heart than try to help.

Full essay here.

Dust Bunny

Directed & Written by Bryan Fuller

Fuller’s always been an imaginative, innovative mind, which is hard to deny if you’ve seen Hannibal, American Gods, or Pushing Daisies, so it’s no surprise Dust Bunny is an incredibly creative work of art. More than innovation and creativity, Dust Bunny is a thoughtful, heartfelt, and beautifully bizarre look at how the worlds of children and adults collide. Most of all, Fuller’s film sweetly addresses the idea of finding a chosen family, no matter who they are or how we find them; it’s not solely about blood or family ties, it’s more often about who is willing to love us they way we deserve to be loved and what people are willing to put on the line to protect us.

Full essay here.

Pingback: From Our Members’ Desks (Jan. 12, 2026) – Online Film Critics Society