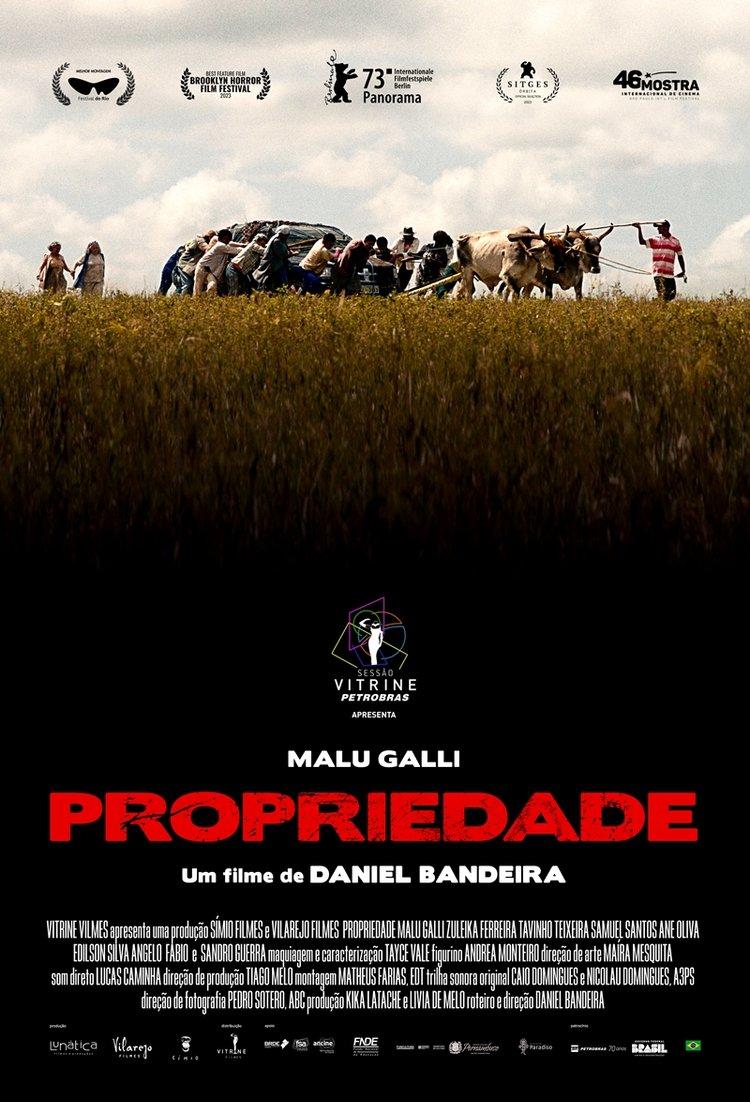

Property (2024)

Directed & Written by Daniel Bandeira

Starring Malu Galli, Carlos Amorim, Anderson Cleber, Zuleika Ferreira, Ângelo Fàbio, Sandro Guerra, Roberta Lúcia, Amara Rita Magalhães, & Marcílio Moraes.

Drama / Thriller

★★★★1/2 (out of ★★★★★)

DISCLAIMER:

The following essay contains

BIG SPOILERS!

Daniel Bandeira’s Property takes on the shape of a home invasion thriller while developing significant themes with decades of history behind them concerning the social and political landscape surrounding private property in Brazil. The story starts by introducing Tereza (Malu Galli), a former designer who’s become nearly agoraphobic in the wake of a violent attack and hostage situation. She’s getting back out into the world, though. When she and her husband head to their farm to get away from the city a bit, she winds up in the midst of a violent revolt carried out by the farm workers who’ve just been informed they’re being let go and kicked off the land due to a new capitalist investment by the land owner, Tereza’s husband. Tereza’s little getaway in the country turns into a fight for survival, and the only place she has to hide is in her husband’s armoured vehicle, as the workers outside its locked doors figure out how to get to her.

Daniel Bandeira’s Property takes on the shape of a home invasion thriller while developing significant themes with decades of history behind them concerning the social and political landscape surrounding private property in Brazil. The story starts by introducing Tereza (Malu Galli), a former designer who’s become nearly agoraphobic in the wake of a violent attack and hostage situation. She’s getting back out into the world, though. When she and her husband head to their farm to get away from the city a bit, she winds up in the midst of a violent revolt carried out by the farm workers who’ve just been informed they’re being let go and kicked off the land due to a new capitalist investment by the land owner, Tereza’s husband. Tereza’s little getaway in the country turns into a fight for survival, and the only place she has to hide is in her husband’s armoured vehicle, as the workers outside its locked doors figure out how to get to her.

Bandeira smartly starts Property off by building empathy/sympathy for Tereza, portraying her as someone seemingly innocent who’s already survived one violent event and gets tossed right back into another even worse than the first. The film’s emotions don’t quite lie with Tereza and her life of privilege; its heart sits more closely with the exploited and violated landless workers being shuffled off private property so it can be made even more exclusive. The Marxism begins right from the moment the film’s title hits the screen, as tall, looming private property gates close, setting an ominous tone for all that’s about to occur; this image figuratively bleeds exclusion and class division before the blood literally flows later. Property doesn’t pull many punches. It hits far, far harder, and probes much deeper, than any Marxist-leaning story you’ve caught onscreen in recent memory. Property dramatises the politics of land and landlessness in Brazil; there’s a lot of important history related to land/landless in which the film finds context. Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra (MST; known as the Landless Workers’ Movement in English) was founded in January 1984, a social movement inspired by Marxism and aimed at land reform. MST’s goals have been to give poor workers access to land. They’re socially active in raising awareness about social issues that are barriers to land ownership, from sexism and racism, to income inequality, monopolisation, and more. MST believes, as the Brazilian Constitution of 1988 stated, that land should fulfil a social function. Only five years after MST officially formed, 19 members were killed by gunfire, 400 were injured, and 22 were imprisoned in 1989 during the Santa Elmira massacre. In 1996, another 19 members of MST were shot dead and nearly 70 more were injured by Pará state military police, known as the Eldorado do Carajás massacre. A year later in 1997, there were two dozen similar violent confrontations with police and land owners that resulted in deaths of MST-associated activists. But it’s not all just past history, either. Less than a decade ago in 2017, police killed 10 MST-associated activists on the Santa Lúcia farm in Pau d’Arco, Pará following an eviction order; the cops claimed self defence while witnesses said there was no violence from activists, nor were the activists warned by the cops. All of this is the sociopolitical context in which Property‘s tension boils over, after the mob of workers being booted off the land where they’ve been working and living take power back into their own hands by violent means.

Property dramatises the politics of land and landlessness in Brazil; there’s a lot of important history related to land/landless in which the film finds context. Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra (MST; known as the Landless Workers’ Movement in English) was founded in January 1984, a social movement inspired by Marxism and aimed at land reform. MST’s goals have been to give poor workers access to land. They’re socially active in raising awareness about social issues that are barriers to land ownership, from sexism and racism, to income inequality, monopolisation, and more. MST believes, as the Brazilian Constitution of 1988 stated, that land should fulfil a social function. Only five years after MST officially formed, 19 members were killed by gunfire, 400 were injured, and 22 were imprisoned in 1989 during the Santa Elmira massacre. In 1996, another 19 members of MST were shot dead and nearly 70 more were injured by Pará state military police, known as the Eldorado do Carajás massacre. A year later in 1997, there were two dozen similar violent confrontations with police and land owners that resulted in deaths of MST-associated activists. But it’s not all just past history, either. Less than a decade ago in 2017, police killed 10 MST-associated activists on the Santa Lúcia farm in Pau d’Arco, Pará following an eviction order; the cops claimed self defence while witnesses said there was no violence from activists, nor were the activists warned by the cops. All of this is the sociopolitical context in which Property‘s tension boils over, after the mob of workers being booted off the land where they’ve been working and living take power back into their own hands by violent means.

Like the workers in Bandeira’s film being kicked off the land so a hotel can be constructed, 600 Brazilian households in Passo Real were dislocated in 1974 to make way for construction of a hydroelectric dam, and not long later another 300-1,000 households were dislocated from the Kaingang Indian Reservation in Nonoai. These events were part of what mobilised so many people in Brazil and helped form the MST a decade later. In Property, the workers try their best to keep an activist spirit without going overboard, except it eventually devolves into pure violence; however, that violence isn’t unearned. If you’re not coming from a Marxist perspective yourself as a viewer, the violence the workers commit against Tereza and her husband Roberto, as well as the foreman Renildo, might seem shocking to you. Yet Antonia delivers a stunning monologue summing up the violence done to the workers in the name of private property: “I‘ve bought this farm. Some of you bought it with your voice, like Zildo. Some bought it with a finger. Some even bought with their skin. Or an eye. I bought it with a child. With a husband. Now it‘s mine.” Her cutting words illustrate the uselessness of money in the face of the bodily price paid by the people who actually work the land instead of owning it. Antonia’s monologue begs the question of what’s worth more ultimately: pieces of paper (money) that have no inherent value aside from what the government determines, or the bodies, the minds, the dignity, and the survival of living people? While many might feel empathy for Tereza since she’s actually an artist, a designer, and isn’t the wealthy land baron her husband appears to be—especially after the opening scene depicting her being violently held hostage by a man on the street—she’s a wonderful example of how even the supposedly progressive world of the arts can play accomplice to the world of capitalism, land ownership, and private property. Early on, Tereza’s daughter urges her to go back to being a creative instead of doing the work she’s currently doing, presumably something related to her husband’s capitalist interests. In the end, as Tereza finds herself being buried alive within her husband’s armoured vehicle, the only thing she can do is accept her fate and post old design sketches around her, like the ghosts of her old life haunting her while she succumbs to the results of the new life she chose. She had a choice to be someone and something else but chose to align herself with old money; her husband Roberto explicitly says he inherited his wealth, admitting he’s done nothing to earn the land: “This is my land. It belonged to my family and now it‘s mine.” And she chose to be part of everything that inherited wealth begets.

While many might feel empathy for Tereza since she’s actually an artist, a designer, and isn’t the wealthy land baron her husband appears to be—especially after the opening scene depicting her being violently held hostage by a man on the street—she’s a wonderful example of how even the supposedly progressive world of the arts can play accomplice to the world of capitalism, land ownership, and private property. Early on, Tereza’s daughter urges her to go back to being a creative instead of doing the work she’s currently doing, presumably something related to her husband’s capitalist interests. In the end, as Tereza finds herself being buried alive within her husband’s armoured vehicle, the only thing she can do is accept her fate and post old design sketches around her, like the ghosts of her old life haunting her while she succumbs to the results of the new life she chose. She had a choice to be someone and something else but chose to align herself with old money; her husband Roberto explicitly says he inherited his wealth, admitting he’s done nothing to earn the land: “This is my land. It belonged to my family and now it‘s mine.” And she chose to be part of everything that inherited wealth begets.

The most damning moment for Tereza is when she’s out of the vehicle then has to rush back inside, just as the workers come for her, and as she quickly shuts the door she ends up slamming it on a young boy’s hand. The workers are forced to the cut the boy’s arm off to flee since cops are on the horizon. For me, this has shades of previous atrocities committed in the name of land, specifically King Leopold II’s rule in the Congo Free State, marked by brutality like chopping off hands to be presented in baskets to European commanders. It’s all the more sad because it’s the workers themselves who have to do it in an effort to evade state repercussions for their revolt. Tereza isn’t King Leopold II, but when a child’s arm has to be hacked off due to your privileged safety being upheld, you’re not much better than those European commanders and the baskets of mutilated hands at their feet.

There are many great little touches throughout Property that I haven’t referenced, like Antonia savouring a cup of coffee, not removed from the products of labour like the bourgeois who take it all for granted, or the subplot of workers being slowly poisoned by pesticides (“You‘re just fucking us up!”), or how Tereza bribes a young woman amongst the workers with money, design sketches, and expensive clothes. There’s even a perfect scene when Tereza’s husband insists, even as he’s lying wounded and positioned physically ‘lower’ in the frame than everyone else, that he still be called Mr. Roberto; the obsessive delusions of the bourgeois class on full display. Everything in Bandeira’s film is purposeful, playing into its clear Marxist themes about how viciously class is divided in Brazil, and how those divides are typically upheld by land ownership. This one’s not for the faint of heart, though it isn’t especially explicit in its violence. I only mean that those who are deeply attached to their ideas about land ownership and private property will have their beliefs challenged, and even shaken, after they witness the events depicted in Property.

Pingback: This Week at the Movies (Jul. 12, 2024) – Online Film Critics Society