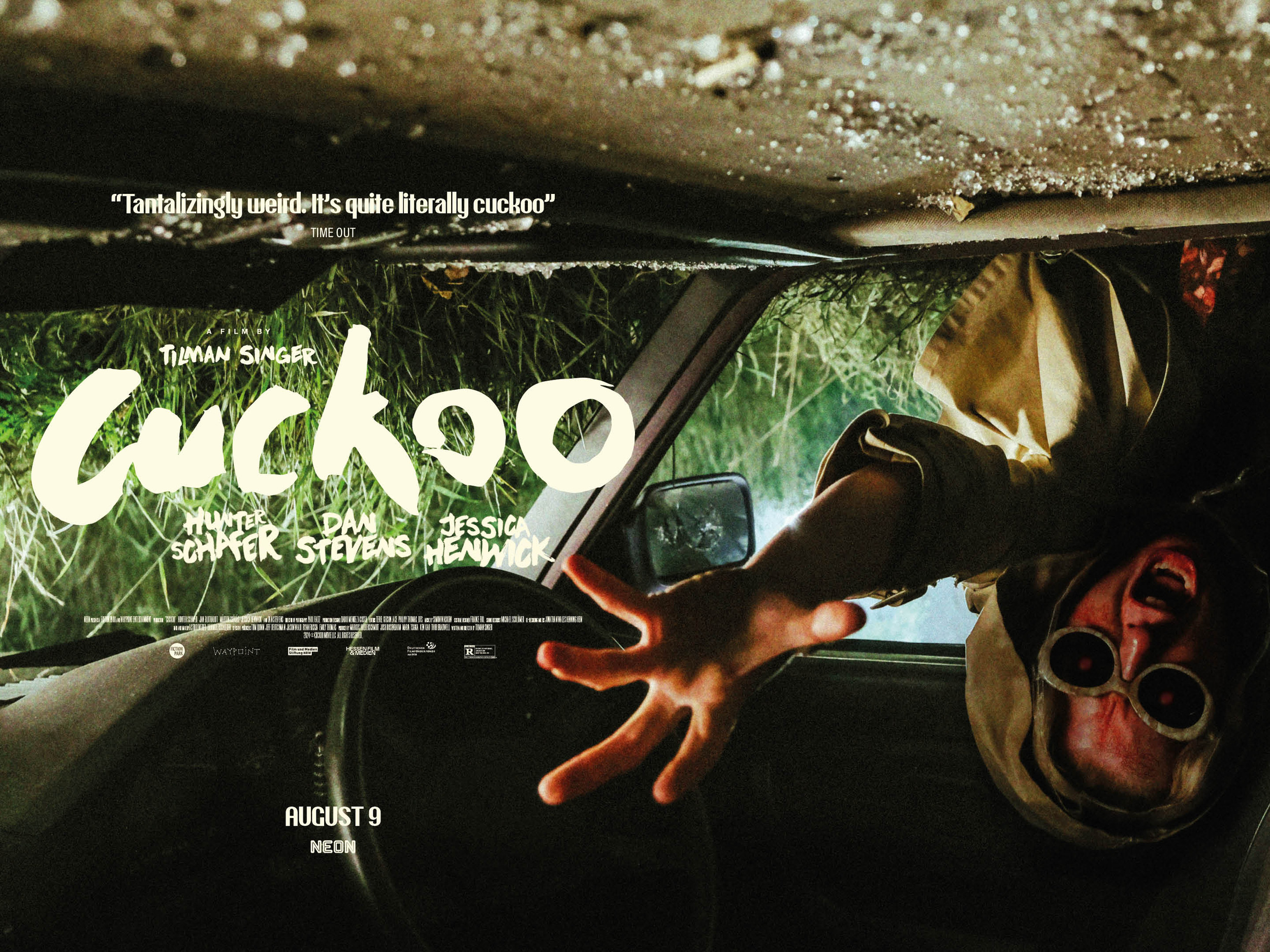

Cuckoo (2024)

Directed & Written by Tilman Singer

Starring Hunter Schafer, Dan Stevens, Jan Bluthardt, Marton Csokas, & Jessica Henwick.

Horror / Mystery / Thriller

★★★★1/2 (out of ★★★★★)

DISCLAIMER:

The following essay contains

SIGNIFICANT SPOILERS!

Turn back, or be forever spoiled.

The weird, wild, and wholly disturbing Cuckoo from Tilman Singer takes us to the Bavarian Alps in Germany where Gretchen (Hunter Schafer) has moved with her father Luis (Marton Csokas) and his new family, wife Beth (Jessica Henwick) and their daughter Alma (Mila Lieu). They’ve gone to live at a strange resort overseen by Herr König (Dan Stevens), who’s one-part Freud, one-part Dr. Moreau. Naturally it’s not long until strange occurrences begin. König warns Gretchen not to travel alone on the road at night. But she doesn’t listen and has a run-in with a strange, violent woman, which opens her eyes to horrifying truths about the resort, König, and even her own family.

Cuckoo is a frightening exploration of a world in which women’s bodily autonomy has been further denied and heteronormativity has warped into perhaps its most perverse, albeit fantastical form. There’s also an inescapable fascism Singer locates in men like König who seek to control the act of reproduction; a fascist desire to do anything necessary to be the ultimate patriarch. Yet, in the end, Cuckoo offers hope and queer possibilities beyond an existence gripped by heteronormative terror. The revelation of what’s actually happening at König’s resort is a sick reality, beginning with strange moments like the wild woman chasing Gretchen, who hunts other women, lays them down, then pulls something from between her legs to put inside the now-hypnotised victim. We see more and more of the cuckoo bird itself, from a photo on König’s dashboard in his car, to the birds themselves outside. Eventually we discover why the cuckoo is so important to this contemporary mad scientist: many cuckoos are known as “brood parasites” because they lay eggs in the nests of other birds and let their offspring be raised by others, and do so by ‘tricking’ their host to reproduce. König sees this as an “approach to family [that] is beyond human comprehension.” He later eerily refers to “laying ceremonies,” which are, without his desperately sociological title, actually assisted rapes accomplished between the awful cuckoo women and König’s team. Perhaps the most unsettling line he utters is when he tells Gretchen, in reference to young Alma: “Let her go—she is destined to be a mother.” König’s desire for hetero-patriarchal control knows no ethical bounds, not even the legal age of consent, or consent at all.

The revelation of what’s actually happening at König’s resort is a sick reality, beginning with strange moments like the wild woman chasing Gretchen, who hunts other women, lays them down, then pulls something from between her legs to put inside the now-hypnotised victim. We see more and more of the cuckoo bird itself, from a photo on König’s dashboard in his car, to the birds themselves outside. Eventually we discover why the cuckoo is so important to this contemporary mad scientist: many cuckoos are known as “brood parasites” because they lay eggs in the nests of other birds and let their offspring be raised by others, and do so by ‘tricking’ their host to reproduce. König sees this as an “approach to family [that] is beyond human comprehension.” He later eerily refers to “laying ceremonies,” which are, without his desperately sociological title, actually assisted rapes accomplished between the awful cuckoo women and König’s team. Perhaps the most unsettling line he utters is when he tells Gretchen, in reference to young Alma: “Let her go—she is destined to be a mother.” König’s desire for hetero-patriarchal control knows no ethical bounds, not even the legal age of consent, or consent at all.

Historical bio-experimentation cannot be ignored since Cuckoo is not only filmed but set in Germany, more specifically the country’s Bavarian Alps, which urges that we consider the long shadow cast by Hitler and the Nazis. Josef Mengele’s gruesome experiments on Jewish prisoners during the Holocaust are the most obvious reference to come to mind, but the Schutzstaffel (SS) obsessions with the heteronormative family were also part of Nazi experimentation merged with terrible nationalism. The Lebensborn (meaning ‘fount of life’) was an SS-led, secret initiative aimed at increasing the number of supposedly ‘racially pure’ children considered Aryan by Nazi Germany, so they not only promoted typical heteronormative living for families (and purged gay people during the Holocaust since this went against their hetero-obsessed mission), they went as far as kidnapping children who were deemed ‘racially valuable’ to the project. Considering all this, it may be a tad more than the fact Singer is German that he situates König’s lair in the same mountains where Hitler went for holiday at the Berghof, which—curiously for the purposes of this writing—is colloquially known as The Eagle’s Nest. Hmm.

The saving grace in Singer’s film to combat König’s hetero-patriarchal horrors is its queerness. Cuckoo‘s queerness, similar to the queer elements in Singer’s previous stunning film Luz, is only briefly explored onscreen, yet its presence within this plot and story is significant since everything revolves around Herr König’s hideous experiments in heteronormative birth. Gretchen meets a woman called Ed (Àstrid Bergès-Frisbey), whose name alone quietly defies the gender norms and heteronormative order of König’s creepy world. They quickly connect in their apathy about the place and make out. They try to get away together, but one of the cuckoo women hunts Gretchen down, refusing to allow her any escape from the horrors yet to come. Finally, after a brutal confrontation with König, it’s Ed there to help Gretchen and Alma flee. The two queer women escape that place’s nightmarish heteronormativity, simultaneously teaching young Alma there’s possibility for life, and family, beyond what hetero-obsessive men insist is acceptable. A sickening reversal of power and sexuality occurs in Cuckoo: in Herr König’s twisted nest, the women are the ones committing an act of sexual assault on other women by forcibly implanting eggs inside them, then the icky terror amplifies when the husbands/lovers of these women unknowingly fertilise the implanted eggs. It’s rape on a diabolical level. Everyone, regardless of gender, falls under König’s spell, not unlike Germany once fell under the patriarchal spell of another awful man who sought to transform not just the nation but the face of German families themselves. (Remember that while Herr just means Mr. most of the time, its etymology likewise connects it to words like ‘master, owner, ruler.’)

A sickening reversal of power and sexuality occurs in Cuckoo: in Herr König’s twisted nest, the women are the ones committing an act of sexual assault on other women by forcibly implanting eggs inside them, then the icky terror amplifies when the husbands/lovers of these women unknowingly fertilise the implanted eggs. It’s rape on a diabolical level. Everyone, regardless of gender, falls under König’s spell, not unlike Germany once fell under the patriarchal spell of another awful man who sought to transform not just the nation but the face of German families themselves. (Remember that while Herr just means Mr. most of the time, its etymology likewise connects it to words like ‘master, owner, ruler.’)

Leaving König’s metaphorical comparison to German history would be foolish since we’re living in a world, post-Roe v. Wade in America particularly, that still denies women the autonomy to live in their own skin and make important choices about their own bodies. Cuckoo is a dark, depraved parable about the world we live in currently, perhaps suggesting through its potential connections to Germany’s past that while time has moved forward things have not necessarily changed too much when it comes to the hetero-patriarchal control men seek not just over women but over the very concept of family. The one hope comes in the film’s finale: maybe, just maybe, the lesbians will save us from ourselves.