Infirmary (2026)

Directed by Nicholas Pineda

Screenplay by Katy Krauland

Starring Paul Syre, Mark Anthony Williams, & Danielle Kennedy.

Horror

★★★★ (out of ★★★★★)

DISCLAIMER:

The following essay contains

SLIGHT SPOILERS!

Turn back or be spoiled forever.

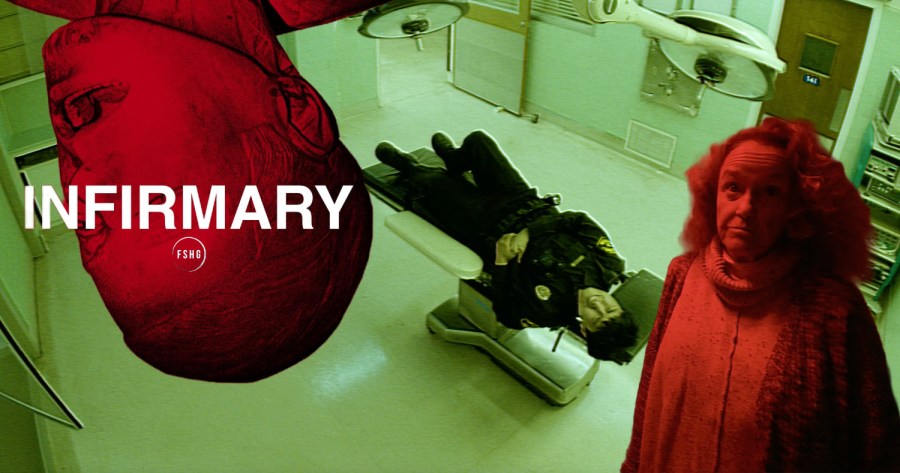

Nicholas Pineda’s Infirmary is a found-footage horror set in a rundown hospital where Ed (Paul Syre), a young former Marine, is hired as a security guard. Ed’s got his own ghosts, but he’s told by head security man Lester (Mark Anthony Williams) about the hospital’s spooky history, involving crazed owners and disturbing practices. The guards are all alone in the hospital except for an administrator named Ms. Downey (Danielle Kennedy). At first, Lester plays a few little pranks on Ed to bring him into the fold. As Ed’s first night of employment progresses, he deals with an intruder lurking in the shadows, creepy mannequins that never seem to stay where they’re stored, then, later, things that are much more terrible.

Infirmary is an unsettling piece of found footage that doesn’t get too bogged down in the actual found footage aspect like other films in the subgenre, relying on CCTV and security guard body cams to follow the plot. It’s also a horror film incapable of ignoring the state of America outside the hospital’s walls, as Ed’s military service becomes a focal point. Like certain aspects of the hospital itself, Ed feels haunted, and while the hospital’s inner world is dictated by its former owners, so is Ed’s mind dictated by his former owners, the United States Armed Forces. In the end, Ed’s swept up in a gothic nightmare simply due to being unfortunate enough to get hired at the wrong hospital. Maybe that’s the real horror of Infirmary—not the horrors of what’s lurking in the hospital’s basement, but the horrors of a job market that forces damaged people into taking whatever work is available to them, no matter if it’s in an old building with an ugly history full of malevolent forces.

Underneath the creeps, Infirmary touches briefly on law enforcement’s obsession with race, even when it’s a member of a historically marginalised racial community. This is evidenced by Lester’s use of “Vietcong” when referring to Ed during their initial meeting at the hospital. For those who don’t know, the Vietcong (VC) were communist guerrillas who fought against the South Vietnamese government and U.S. intervention from 1954 until the end of the Vietnam War in 1975. Not only does Lester liken Ed to a Vietcong for ‘sneaking up’ on him, he goes so far as to question Ed’s patriotism despite the fact Ed was a Marine and even mentions that as a kid he saw footage of 9/11 that inspired him to later join the military. Lester asks if Ed is a “defector” and frames it with the question: “Are you some kind of Chelsea Manning?” In a film that’s really only focused on haunting terrors, Infirmary manages to engage with aspects of American culture that are very relevant to the current moment in time.

Underneath the creeps, Infirmary touches briefly on law enforcement’s obsession with race, even when it’s a member of a historically marginalised racial community. This is evidenced by Lester’s use of “Vietcong” when referring to Ed during their initial meeting at the hospital. For those who don’t know, the Vietcong (VC) were communist guerrillas who fought against the South Vietnamese government and U.S. intervention from 1954 until the end of the Vietnam War in 1975. Not only does Lester liken Ed to a Vietcong for ‘sneaking up’ on him, he goes so far as to question Ed’s patriotism despite the fact Ed was a Marine and even mentions that as a kid he saw footage of 9/11 that inspired him to later join the military. Lester asks if Ed is a “defector” and frames it with the question: “Are you some kind of Chelsea Manning?” In a film that’s really only focused on haunting terrors, Infirmary manages to engage with aspects of American culture that are very relevant to the current moment in time.

Another interesting aspect of Infirmary is how the mannequins and Ed are subtly connected in that the use of the mannequins can be read as juxtaposed with American soldiers. The mannequins were used and discarded once their purposed was served, now they’re like ghostly figures in the bowels of the hospital left to haunt its corridors, similar to how soldiers like Ed are used and discarded after their service then return to civilian life as ghosts of their former selves. One particularly great scene in this regard is when Ed seems to go into a kind of trance, or maybe just an extended bit of roleplay, and seems to relive bits of his time in the Marines, from an injury to being on the frontlines firing his weapon. At one point he barks “Reporting for duty” then drops to the ground for pushups. His life at home is haunted by his time abroad as part of the Marine Corps. The spirits inside the mannequins have effectively been abandoned by their creator, as we hear that Mrs. Wilshire, one of the hospital’s owners, disappeared, just as Ed’s been abandoned by the military and the government due to what he calls “bureaucracy and stuff” related to his injury.

Both Lester and Ed have been forced to work at the creepy old hospital in Infirmary due to their prior careers: Ed’s there because an injury he felt he couldn’t report immediately has messed up his post-Marine Corps life, and Lester’s there because he was asked to leave the police force potentially due to alcoholism. These are two men who have been damaged by America in different ways; one at home, the other abroad. This also makes them prime candidates to be seized by the hospital’s malignant energy, given Mrs. Wilshire’s previous strange experiments. Infirmary is a solid enough horror without any of the extra social themes, and it only gets more sinister with each passing moment until a final Blair Witch Project-like image points to a morbid fate. Considering the film’s peripheral ideas about America, Infirmary is a more complex found footage horror than most. The film’s penultimate scene features a script related to the FBI’s investigation into Ed’s disappearance which, to me, only further suggests America’s dastardly forces are at work in an attempt to blame a veteran rather than actually help or even save him. Pineda spins what could be a run-of-the-mill found footage horror film into something darker and more unsettling on a much larger scale than just another creepy old hospital.

Pingback: This Week at the Movies (Jan. 23, 2026) – Online Film Critics Society