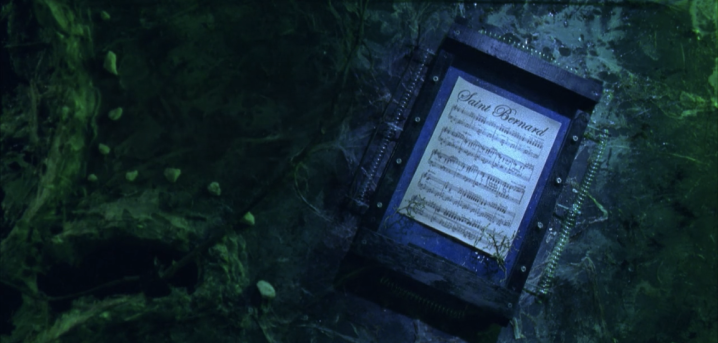

Saint Bernard. 2013 (released by Severin Films in 2019). Directed & Written by Gabe Bartalos.

Starring Jason Dugre, Katy Sullivan, Peter Iasillo Jr., Jack Doroshow, Bob Zmuda, Warwick Davis, George Clayton Johnson, & Albert Strietmann.

Center Ring Entertainment

Not Rated. 97 minutes.

Fantasy / Horror

★★★1/2

Most serious horror fans will recognise the name Gabe Bartalos. He’s been responsible for many glorious genre creations over the past few decades. He started in the mid-to-late 1980s working as an assistant and crew member doing special makeup effects for films like Crawlspace, Friday the 13th Part VI: Jason Lives, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2, and From Beyond. Frank Henenlotter would later gave him the opportunity to design and execute effects for Brain Damage in ’88, leading to a collaboration that would go on to last over 20 years, including Henenlotter’s Basket Case 2, Frankenhooker, and his 2008 film Bad Biology.

Most serious horror fans will recognise the name Gabe Bartalos. He’s been responsible for many glorious genre creations over the past few decades. He started in the mid-to-late 1980s working as an assistant and crew member doing special makeup effects for films like Crawlspace, Friday the 13th Part VI: Jason Lives, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2, and From Beyond. Frank Henenlotter would later gave him the opportunity to design and execute effects for Brain Damage in ’88, leading to a collaboration that would go on to last over 20 years, including Henenlotter’s Basket Case 2, Frankenhooker, and his 2008 film Bad Biology.

Bartalos has worked with other legends in the business, such as Stuart Gordon, Joe Dante, Rick Baker, and Tobe Hooper. He’s also provided effects for the likes of Matthew Barney, whose Cremaster Cycle is a moving artistic masterpiece. Not to mention he was the mind behind the grotesque face Warwick Davis wore as the villain in the 1993 horror-comedy Leprechaun, which provided many young folks of Father Gore’s generation with chills and St. Paddy’s Day thrills.

Safe to say Gabe hasn’t only had an exciting, prolific career, he’s a fantastic artist in his own right, and working with such towering names in the horror genre only helped him to grow, hone, and perfect his skills as an effects driven creator.

That’s where Saint Bernard comes in— a new vision of madness bestowed upon us by Bartalos’s wonderfully strange mind. It was originally released in 2013, only now finally being distributed by Severin Films. It’s a culmination of what the FX master and director has done over the years, marrying innovative genre work, like what he’s done for Henenlotter, with the intensely cerebral-style effects narratives such as what he did in collaboration with Barney. Despite those influences, it’s a mad cinematic ride that crawled out of his brain alone.

This isn’t a film for everybody. For those who get hooked by the unbelievable imagery and fantastical story, there’s actually much more narrative hiding underneath the visual and aural insanity than might initially appear. A simple plot— involving a conductor named Bernard (Jason Dugre), who spirals into a horrific mental breakdown— actually contains layers of meaning. Father Gore’s going to unpack his own personal reading of Saint Bernard, involving trauma’s effects on a victim’s reality.

Something the viewer initially becomes aware of is a thin veil between Bernard’s past and present. He shifts from waking life to dreams of his past intermittently throughout. This seamless bridge into Bernard’s past is significant, because all his issues as an adult are connected to events in his childhood.

Something the viewer initially becomes aware of is a thin veil between Bernard’s past and present. He shifts from waking life to dreams of his past intermittently throughout. This seamless bridge into Bernard’s past is significant, because all his issues as an adult are connected to events in his childhood.

Specifically, Bernard’s relationship to his Uncle Ed informs much of the trauma he experiences. An early scene shows him, as a boy, go from a music shop instantly to a strange, Alice in Wonderland-like house where he performs as a conductor for a bunch of other kids. Afterwards, he goes inside and sits with Uncle Ed, who helps him practise with his baton. Bernard suddenly transform into his adult self via one swift motion as the camera pans around behind the uncle, visually conveying the upsetting link between his childhood and his life as a damaged adult.

An underlying theme is the effect of childhood abuse on a victim when they become an adult. Slowly, this aspect of Bernard’s story pieces together. There are several early references to addiction. During one scene, Bernard walks through a landscape of rubble. Maybe it’s the rubble of his life. There’s a sea of broken glass, also pipes, pills, Visine bottles, and other drug-related paraphernalia. Bernard walks across it all over what looks like a wooden window frame, the same as a circus performer would inch across a tightrope— the figurative tightrope he walks, struggling through addiction and the vague memories of his abuse.

Another scene later depicts him conducting. Bernard chokes a little, and before the performance can begin he opens his arms, letting a ton of paraphernalia tumble to the floor around him, dramatically revealing his drug use to the crowd. He becomes what Bartalos himself called a “Fleshsicle“— symbolic of how he feels, envisioning himself as a low, disgusting, worm thing— after one of the best head explosion effects since David Cronenberg’s Scanners. Then he wriggles out of there, away from the embarrassment. These two scenes show that part of Bernard’s struggle comes from addiction, which changes our perception of the world, altering the lens through which we see and experience reality.

Childhood abuse— which often leads to addiction(s)— also distorts reality. The world of the film appears to the viewer as it does to the protagonist. Due to the abuse (which we’ll return to in detail shortly) he experienced as a boy, Bernard, as an adult, sees the world like he would when he was a child: big, cartoonish, confusing, grotesque, inexplicable, and, all too often, scary.

One of the best sequences in this regard is the Kafkaesque police station, where Bernard meets the nasty Chief (Peter Iasillo Jr) and goes through the disorganised, decaying system of bureaucracy. The Chief, pictured below, is a sight, and embodies the corrupt, bloated, and wretched aspects of the police as a state institution. To Bernard— effectively a boy trapped in a man’s body— he appears oversized and terrifying. This is a theme with authority figures and symbols of power, appearing to our protagonist as exaggerated caricatures that aren’t funny, rather they’re ghastly images.

In an earlier scene, Bernard wanders into a church, where he sits in a pew among the congregation while Father Steele (played by the enigmatic Bob Zmuda) rambles: “The Lord wants me to be financially stable.” When Bernard doesn’t have any cash to offer, he’s attacked by the priest, who sees him wearing a suit made of bills. He’s chased into the street, where people tear bills off him without concern for his screams. Then, like the money itself comes to life, famous American figures from right off the bills are in the street fighting— Bernard witnesses President Abraham Lincoln, President Andrew Jackson, and one of the Founding Fathers, Benjamin Franklin, battle like a strange football team on the pavement of a random lot. These three American icons appear not like their typical history book selves, as intellectuals, but as rage-filled figures of commerce and war. More examples of the warped world Bernard lives in as an adult, unable to let go of his child-like perspective.

“You’ll always be my favourite”

There’s a large amount of wood imagery in Saint Bernard. Father Gore sees it as a surreal symbol of construction, in the sense of a construct (i.e. to construct is to build / a construct is a theory with various conceptual elements). One of the first images is a patchwork of wood making an abstract construction, from which a conductor’s baton is whittled and given to young Bernard. Later, adult Bernard encounters wood in various forms: in the streets of Paris, he’s trapped by a wooden structure that soon weighs him down; he encounters an odd man in the desert pushing a baby carriage made of wooden bits, containing an unseen baby spitting blood at him; and then there’s his encounter with a guardian angel-type character, Othello (Warwick Davis), who grants him “a little more time” to figure out his surreal journey.

There’s a large amount of wood imagery in Saint Bernard. Father Gore sees it as a surreal symbol of construction, in the sense of a construct (i.e. to construct is to build / a construct is a theory with various conceptual elements). One of the first images is a patchwork of wood making an abstract construction, from which a conductor’s baton is whittled and given to young Bernard. Later, adult Bernard encounters wood in various forms: in the streets of Paris, he’s trapped by a wooden structure that soon weighs him down; he encounters an odd man in the desert pushing a baby carriage made of wooden bits, containing an unseen baby spitting blood at him; and then there’s his encounter with a guardian angel-type character, Othello (Warwick Davis), who grants him “a little more time” to figure out his surreal journey.

The image featured above— depicting Bernard in the desert, stuck between a small mangled tree and a wooden box like a square Jenga puzzle— acts as a perfect metaphor for how wood represents a construct in Bernard’s nightmarish world, in that wood can become what you construct it to be, much like life: it can either become a charred, destroyed stump, or it can be made into a perfect, albeit complicated and intricate thing like the wooden puzzle box.

Yet the scariest image of wood links directly to the abuse Bernard suffered as a boy— the trauma that informs much of the imagery and symbolism surrounding him. First of all, he faces his Uncle Ed, after all these years, in an unfinished wooden space, like an abstract collection made up of wooden pieces— it’s in this construct he confronts what constructed his life’s path. Worse than that, Bernard kneels in front of his Uncle Ed, only for the old man to reveal a bulging erection made of raw wood, as if it were the natural, mossy stump of a tree. During this scene, Uncle Ed all but outright reveals the molestation of his nephew, calling the boy his “favourite” and smashing a picture of Bernard as a child. He transforms into a predatory wolf made of musical instruments that form organic parts of his body, until he’s not even human anymore. This sequence involves Bernard recalling all the psychological terror and physical horror his perverted uncle inflicted on him, and he fights against the surreal monster formed out of his painful repressed memories. In this final confrontation, all of the symbolism wrapped up in Bernard’s trauma— music, wood, being preyed upon by his uncle, and maybe even more depending on how closely you read into certain images— explodes in a burst of mad catharsis.

“What did you want to be?”

Inherent in surrealism and absurdist cinema is the idea that there are many readings of the material. Bartalos had his own ideas about what the imagery and symbolism of Saint Bernard means when he made the film. Now, he passes the film onto his viewers, who’ve got the chance to make their own meaning out of its strange, hilarious, and horrifying journey. This ambiguity allows us the freedom to interpret the film on our own terms, through our own perspectives. If you enjoy a surreal horrorshow and don’t feel like reading too deeply into it, outside the basic ‘artist goes mad’ premise, then Saint Bernard works perfectly fine on that level, too.

Inherent in surrealism and absurdist cinema is the idea that there are many readings of the material. Bartalos had his own ideas about what the imagery and symbolism of Saint Bernard means when he made the film. Now, he passes the film onto his viewers, who’ve got the chance to make their own meaning out of its strange, hilarious, and horrifying journey. This ambiguity allows us the freedom to interpret the film on our own terms, through our own perspectives. If you enjoy a surreal horrorshow and don’t feel like reading too deeply into it, outside the basic ‘artist goes mad’ premise, then Saint Bernard works perfectly fine on that level, too.

Bartalos put a lifetime of artistic creation into just under 100 minutes, crafting images the like of which you’ll never see anywhere else. His designs here are as mind boggling and creepy and hideous as anything he’s done for Henenlotter, just as the nightmarish landscapes he creates are as deeply cerebral as the work he did with Barney. Best of all, this is purely his vision, from screenplay to storyboard to cinematography. Even if you take his film at face value, it remains an unforgettable cinematic experience.

Father Gore’s inclined to read the film as a compelling, absurd, and surreal look at how a victim of childhood trauma comes to deal— or, not deal— with its effects later in life. Rather than do what others have done before, Bartalos chose to find a different way to portray a descent into madness, and it’s as wild as it is effective.

Father Gore’s interview with director Gabe Bartalos can be read here.

Pingback: Down a Traumatic Rabbit Hole in SAINT BERNARD | Saint Bernard