Rabid. 1977. Directed & Written by David Cronenberg.

Starring Marilyn Chambers, Frank Moore, Joe Silver, Howard Ryshpan, Patricia Gage, Susan Roman, Roger Periard, Lynne Deragon, Terry Schonblum, Julie Anna, & Gary McKeehan.

CFDC/Dunning-Link-Reitman/The Dilbar Syndicate

Rated R. 91 minutes.

Horror/Sci-Fi

★★★★

As a Canadian, I hold David Cronenberg on a huge pedestal. Not simply for the fact he comes from this great country, also for the fact he was one of the early auteurs behind the camera during his era that was pushing boundaries, exploring places not everybody wanted to go and not every artist wanted to explore. He’s been an inspiration to many filmmakers, but it’s especially relevant how he influenced Canadian filmmakers, many of whom hailed from smaller provinces, smaller towns, and they saw what Cronenberg was doing as a license to get into their own niches, no matter how deep, dark, or disturbing.

As a Canadian, I hold David Cronenberg on a huge pedestal. Not simply for the fact he comes from this great country, also for the fact he was one of the early auteurs behind the camera during his era that was pushing boundaries, exploring places not everybody wanted to go and not every artist wanted to explore. He’s been an inspiration to many filmmakers, but it’s especially relevant how he influenced Canadian filmmakers, many of whom hailed from smaller provinces, smaller towns, and they saw what Cronenberg was doing as a license to get into their own niches, no matter how deep, dark, or disturbing.

Rabid is one of his first feature films, and in a similar vein to his other early foray into sexual-type horror, Shivers.

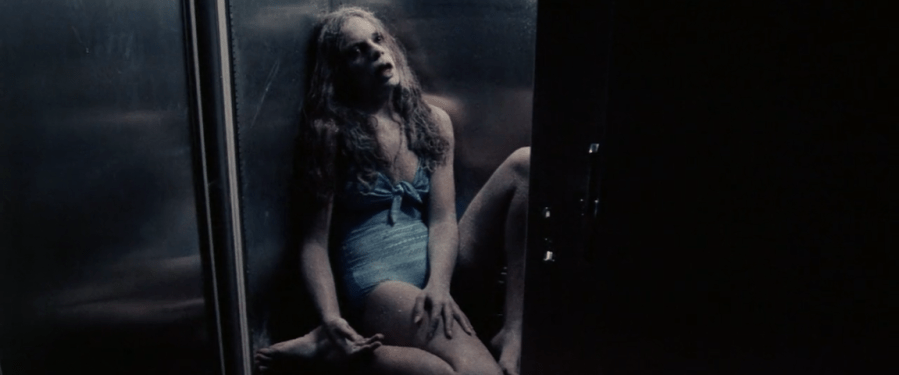

Starring Marilyn Chambers, this is the story of a woman who suffers injuries during a motorcycle accident and then undergoes a experimental plastic surgery to graft back a bit of missing skin. Afterwards, a strange appendage grows from her armpit, and it stings people, infecting them. Soon there’s an epidemic of zombie-like people roaming the city.

Before AIDS was officially discovered and everyone knew its sexual terror, Cronenberg’s film was tackling issues of a hypersexual society, as well as one in which technological developments were being made specifically in relation to the body, no matter if the ethics were caught up at the same level. Culminating in a vicious, unsettling film that showed audiences quickly where this auteur was heading.

You can take Rabid as merely a gross take on the zombie sub-genre of horror. Or you can consider the implications of Cronenberg including medical science at the core of his plot. Because, when considering medical technology and its various advancements, we have to consider our humanity. As in, do they help make us human again after serious accidents and injuries? Do they turn us into something less/more than human, something Other? Rose’s (Chambers) skin graft changes her irreparably. She’s given an experimental treatment, one that’s fresh, new, so there’s no certainty as to what its effects will be later. We see the carelessness of medicine, worried solely with progress and not with consideration of repercussions, ethics, so on. This leads into an epidemic of zombified humans after Rose and her new appendage claims victims.

You can take Rabid as merely a gross take on the zombie sub-genre of horror. Or you can consider the implications of Cronenberg including medical science at the core of his plot. Because, when considering medical technology and its various advancements, we have to consider our humanity. As in, do they help make us human again after serious accidents and injuries? Do they turn us into something less/more than human, something Other? Rose’s (Chambers) skin graft changes her irreparably. She’s given an experimental treatment, one that’s fresh, new, so there’s no certainty as to what its effects will be later. We see the carelessness of medicine, worried solely with progress and not with consideration of repercussions, ethics, so on. This leads into an epidemic of zombified humans after Rose and her new appendage claims victims.

Post-humanism is always at the fore of Cronenberg’s work as a whole. Here, Rose begins struggling with herself, and later in the film, as we near the climax and finale, she struggles to come to terms with her own role in the epidemic she’s unwittingly caused to erupt. Is she still herself? Has she wholly become another person, another thing?

And this leads into yet another concept about humanity, re: the STD-like nature of the infection spread by Rose. If we consider the AIDS connection, we can also see points in the film where the infected citizens are treated how those with HIV were often seen on a societal level. For instance, an official says later in the film: “The victims of this disease are beyond medical help.” This is pretty much how society, for a couple decades at least, saw those living with HIV/AIDS, as incurable, walking dead, and consequently, whether as a conscious effort or not, as less than human.

“I‘m still me“

There’s a further symbolism in the appendage itself, a phallic, living thing that squirms from Rose’s armpit. It’s a monstrous, infectious stinger. Its phallic imagery centres this wholly on a male issue. There’s violence in male sex, the phallus penetrates, pierces, wounds, and in the case of a hypersexual society it leaves behind an illness. In a sense, this phallic stinger is representative of the poisonous violence in the male sex, their perpetual lust, how it works its way into everybody, like an outbreak, an epidemic.

There’s a further symbolism in the appendage itself, a phallic, living thing that squirms from Rose’s armpit. It’s a monstrous, infectious stinger. Its phallic imagery centres this wholly on a male issue. There’s violence in male sex, the phallus penetrates, pierces, wounds, and in the case of a hypersexual society it leaves behind an illness. In a sense, this phallic stinger is representative of the poisonous violence in the male sex, their perpetual lust, how it works its way into everybody, like an outbreak, an epidemic.

Moreover, this epidemic is an overall allegory about STDs, in a pre-AIDS global society where people were frequenting adult movie theatres and other places providing the possibility of carefree sexual contact with random strangers.

This is why Cronenberg situates many of the ‘stings’ in urban spaces: the hospital, the porno theatre, an apartment building, transport trucks leaving the city, et cetera. This is all especially relevant considering the lead role is played by Ms. Chambers. And such a relevant scene epitomises the strong male sexual theme when Rose goes trawling for prey at the porno flick, symbolic of a feeding/breeding ground for sexually transmitted disease; made scarier only by the fact we consider that the threat of AIDS only became known about six years following this film.

It’s in this vein sex is represented as madness, as violence, and ultimately vampiric. There’s an exchange of blood, in how the penis damages the vagina; most significantly if we consider virginity, the violence of how the male appendage violates a physical part of womanhood. There’s the passing of disease, re: the STD symbolism, here in a form of rabies, just as the vampire gene is passed by the bite. The vampire, like the person carrying an STD, goes unknown in the urban landscape. You never know who has the disease, how quickly it then spreads. This is captured well when Rose is at the mall. An old, rabid man attacks somebody. She knows she didn’t infect him, so she begins seeing the consequences of her phallic, fleshy weapon and its thirst for blood while the epidemic unfolds.

Although Cronenberg has shifted slightly from body horror in the past decade or more, we’ll always have Rabid and his other nasty films to remind us he is the single greatest auteur to have worked on artistic representations of the future of bodies. There’s just no doubt of the director’s competency as a filmmaker, and also as a philosopher, or at the very least a theorist drawing on all sorts of contemporary issues we as a postmodern society are facing on a daily basis.

Although Cronenberg has shifted slightly from body horror in the past decade or more, we’ll always have Rabid and his other nasty films to remind us he is the single greatest auteur to have worked on artistic representations of the future of bodies. There’s just no doubt of the director’s competency as a filmmaker, and also as a philosopher, or at the very least a theorist drawing on all sorts of contemporary issues we as a postmodern society are facing on a daily basis.

Before AIDS rocked the world, wreaking havoc on the personal sexual lives, Rabid confronted the scariness of a world where people weren’t considering the implications of unchecked sexual activity, the effects of medical/technological advancements on human beings. It seems to suggest there are untold, horrific consequences to our actions.

Not that sexuality is bad, neither is Cronenberg suggesting advancing our knowledge and use of medical technology is a bad thing. Rather, he’s showing us what happens if we choose to not pay attention to our ethics and morality, letting progress and freedom dictate our way forward.