First Reformed. 2018. Directed & Written by Paul Schrader.

Starring Ethan Hawke, Amanda Seyfried, Cedric Antonio Kyles, Michael Gaston, Victoria Hill, Van Hansis, & Philip Ettinger.

Killer FIlms/Fibonacci Films/Arclight Films

Rated R. 113 minutes.

Drama/Thriller

★★★★★

How do the holy remain so in the changing face of modernity? How can religion extend itself into an age of postmodern cities, pop culture, and the ravages of urbanity and capitalism? Paul Schrader may not have all the answers, though his latest film First Reformed does a fine job of exploring these themes. He’s returned to what he does best: questioning the fabric of America. The thread he pulls on this time is close to his heart, as Schrader grew up in a Calvinist home, part of the Christian Reformed Church. Father Gore suspects Mr. Schrader’s screenplay is a result of many dark nights of faith across decades of life, an accumulated set of anxieties he’s experience about his system of belief.

Ethan Hawke gives a career best performance as Reverend Ernst Toller— a reference to the German Expressionist playwright of the same name. His crisis of faith is brought on by an unfortunate suicide and seeing his First Reformed Church perpetually caught in the gaping maw of capitalist industry. His journey is spiritual and corporeal all at once, confronted with the plight of Mary (Amanda Seyfried), whose husband’s suicide likewise is affecting Toller.

First Reformed questions how the ancient world of tradition and the modern world of capitalism co-exist when they are fundamentally opposed in so many ways. Above all, Schrader examines how extremism can sprout from many dark corners of the human psyche, of which religion is merely one. He digs at the part of all of us which seeks to immerse itself in all aspects of a faith, whether that faith is in religion, activism, business, or anything else. At the heart of extreme belief is a pain— how we choose to soothe it ultimately defines us.

From the start, Rev. Toller appears as the ultimate acolyte of Christ. He occasionally sleeps in the pews of the First Reformed Church. He’s writing in a book for a year as an exercise in prayer, among other things. He tends to the fallen headstones in the graveyard himself, propping them back upright. But soon it’s evident he’s doing so at the expense of his own health.

From the start, Rev. Toller appears as the ultimate acolyte of Christ. He occasionally sleeps in the pews of the First Reformed Church. He’s writing in a book for a year as an exercise in prayer, among other things. He tends to the fallen headstones in the graveyard himself, propping them back upright. But soon it’s evident he’s doing so at the expense of his own health.

Toller’s an alcoholic. He sits at the dinner table and— like every meal is the transubstantiation of Christ’s body/blood into bread/wine— soaks up whiskey from a bowl with bread. We see his alcoholism is related to a damaged past: he pushed his son into the military and feels perpetual guilt because his son died in the Iraq War. He put his faith in institutions he imagined would help him understand the world: church and military. Both failed. First, the military killed his son. Now the church starts failing him. He sees the First Reformed becoming a literal “souvenir shop,” which is the church’s nickname. People treat him more as a tour guide than a reverend. The land itself is owned by a megachurch, Abundant Life— a corporation, not a church, such is the case with all these modern religious institutions.

Moreover, Abundant Life barely fixes anything at the First Reformed except for cosmetic reasons, like when a ceremony is coming up. A perfectly framed shot shows Toller walking into the megachurch with the logo upside down: Schrader could’ve filmed it right-side up, in not doing so he visually subverts Abundant Life to signify Christianity being subverted by capitalism and a general perversion of religion into a commodity. This conflict is drives the theme of the ancient v. the modern.

Church traditions in general refer back to the past. Even the First Reformed Church itself is a relic, filled with souvenirs of the past – the land was part of the Underground Railroad, various parts of the church and items inside are more than a century old – and also filled with real souvenirs from the historical shop. Toller’s church is indicative of a general changing economic role in a lot of churches today, also representing the alienation of modern/postmodern churches from true Christianity in more ways than the effects of capitalism.

“Be strong in the Lord and in His mighty power.

Put on the full armour of God,

so that you can take your stand

against the Devil’s schemes.

For our struggle is not against flesh and blood,

but against the rulers,

against the authorities,

against the powers of this dark world.”

— Ephesians 6:11

Mary becomes part of the plot when her husband Michael (Philip Ettinger) is going through his own crisis of faith due to his extreme activism. Michael cannot deal with the state of the world, neither does he want to bring a baby into it after discovering his wife is pregnant. Rev. Toller tries helping Michael, only to be the one to bear witness to his suicide later. Michael’s situation bridges the gap between the environment and religion.

Mary becomes part of the plot when her husband Michael (Philip Ettinger) is going through his own crisis of faith due to his extreme activism. Michael cannot deal with the state of the world, neither does he want to bring a baby into it after discovering his wife is pregnant. Rev. Toller tries helping Michael, only to be the one to bear witness to his suicide later. Michael’s situation bridges the gap between the environment and religion.

After the suicide, Toller and Mary discover Michael had a suicide vest. They try rationalising his goodness, believing he did not use it because he decided not to when it’s likely he hadn’t gotten the chance. After Michael found out the vest was gone he killed himself. This sends Toller into a worse crisis of faith once he begins questioning the church’s commitment to the environment versus its commitment to big business.

Michael’s environmental activism is concerned with similar things as an authentic belief in religion. Environmental preservation is, in a sense, the act of protecting natural creation, and creation is a central part of Christianity.

In opposition, capitalism involves what’s known as creative destruction, in the sense destruction (i.e. bulldozing forests/tearing down old buildings/etc) is a necessary process for the creation of the new, in turn generating new forms of capital. Creation from these two standpoints is where anxiety lies. Once Toller sees Abundant Life is a wholly corrupt corporate entity not at all interested in Christian goodness, his religious faith merges with the environmental faith of Michael, and his path becomes even more dangerous than it was already.

“The life is more than meat,

and the body is more than raiment.”

— Luke 12:23

Two images are significant in a visual representation of how Toller’s physical state comes to mirror the state of the environment. One depicts him pouring Pepto-Bismol into a glass of whiskey. After he’s ravaged his body with alcoholism, he uses Pepto-Bismol as a patch: it won’t fix anything, it’ll simply delay the painful side effects. The second image is a colourful reflection (seen above) of the Pepto-Bismol’s pink in a shot of an early morning sky, where Toller stands in the foreground and several boats float abandoned, rusting in the water behind him. This shot is representative of another quick fix. Today we know the environment is being destroyed beyond the point of repair, and all we’ve done is put temporary Band-Aids on the problem instead of fixing it. Today, people recycle plastic bags and they try not to drive too much, but the issues the environment faces are far beyond these types of individual, preventative measures, requiring life/society altering changes for anything significant to be done. The sky and the boat ruins v. the whiskey and Pepto-Bismol is an ingenious visual conveying so much theme in a matter of seconds.

Two images are significant in a visual representation of how Toller’s physical state comes to mirror the state of the environment. One depicts him pouring Pepto-Bismol into a glass of whiskey. After he’s ravaged his body with alcoholism, he uses Pepto-Bismol as a patch: it won’t fix anything, it’ll simply delay the painful side effects. The second image is a colourful reflection (seen above) of the Pepto-Bismol’s pink in a shot of an early morning sky, where Toller stands in the foreground and several boats float abandoned, rusting in the water behind him. This shot is representative of another quick fix. Today we know the environment is being destroyed beyond the point of repair, and all we’ve done is put temporary Band-Aids on the problem instead of fixing it. Today, people recycle plastic bags and they try not to drive too much, but the issues the environment faces are far beyond these types of individual, preventative measures, requiring life/society altering changes for anything significant to be done. The sky and the boat ruins v. the whiskey and Pepto-Bismol is an ingenious visual conveying so much theme in a matter of seconds.

Prior to the film’s climax, Toller engages in a non-sexual, physical rite with Mary. This is a way of removing the sacred and the religious from the world of the ancient and bringing it into the postmodern, increasingly secularised world. Rather than performing a sermon for a church of people, removed from the congregation on a pulpit, Toller engages directly, literally, physically with another human being. Through this return to the human he also returns to a purer vision of Christianity, where the natural world takes precedence over today’s capitalist and increasingly urban world. He envisions floating first over beautiful, natural landscapes— one with each other/the world. Suddenly they’re above traffic in the city, floating over roads, a heap of tires reaching to the clouds like a mountain, smokestacks pumping fog, tree cutters devastating forests to make way for urban expansion, trash, and decaying ships in forgotten stretches of ocean. Toller bears witness to the devastation of the natural world through Mary in the same way he bore witness to its personal effects in the grisly suicide of Michael.

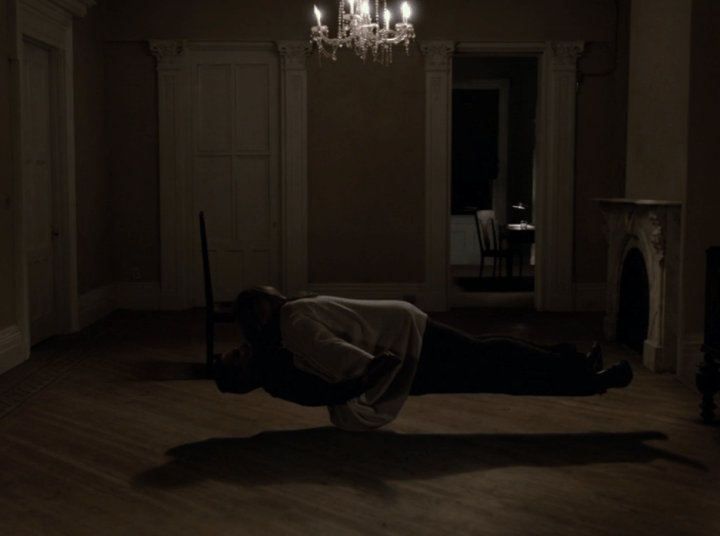

During the film’s climax, the suicide vest returns as further connective tissue between conceptions of extreme faith. Toller makes the decision to blow himself up at the big Abundant Life ceremony for the First Reformed Church. When he sees Mary in the crowd, he opts not to keep the vest on. Instead, he opts for mortification of the flesh. There’s a juxtaposition between violence here, too. As the suicide vest represents an outward expression of pain, encompassing violence done to others, Toller’s act of mortification— barbed wire wrapped around his torso, mirroring the crown of thorns Jesus forcibly wore on the cross— is representative of inner pain, reflecting the pain of the Saviour and affecting only the individual.

Schrader makes the point religion can remain a part of ourselves, we can believe what we believe and not affect others, or we can force our beliefs onto others, possibly hurtfully. Although holding beliefs to oneself can also do damage, it only involves the self rather than pulling others into the pain. The end of the film sees Toller embracing Mary, choosing not to drink a glass of drain cleaner and end his life like Michael did after his extremism was deflated. Like Michael, we can’t be sure Rev. Toller won’t do something drastic. As the screen cuts to black in the midst of a seemingly happy ending, the foreboding score rises up again over the credits, and there lingers a sense Toller hasn’t yet fully escaped his crisis, only put it aside to focus on his personal life.

“Can God forgive us for what we’ve done to this world?”

The way Schrader digs into his topics is always harrowing, in one way or another. First Reformed is no different. It isn’t only harrowing to those who follow a religious faith, in any way, shape, or form. Father Gore hasn’t stopped thinking of the film for a straight week. Its themes are so relevant to the current state of America, not even half of which is discussed in this article. Schrader’s genius here somehow grows after the film is over and the credits end, when we’re left in the dark with only our thoughts and his images occupying the mind.

The way Schrader digs into his topics is always harrowing, in one way or another. First Reformed is no different. It isn’t only harrowing to those who follow a religious faith, in any way, shape, or form. Father Gore hasn’t stopped thinking of the film for a straight week. Its themes are so relevant to the current state of America, not even half of which is discussed in this article. Schrader’s genius here somehow grows after the film is over and the credits end, when we’re left in the dark with only our thoughts and his images occupying the mind.

The story and Hawke’s performance are the sort to fester in your soul.

It isn’t easy to say one Shcrader film is the best because he’s written, and also directed, plenty incredible cinema in the over four decades of his career. First Reformed is up there with Taxi Driver in its searing and (mostly) subtle portrayal of a man divided against himself, the institutions in which he placed his trust and the society which birthed them, as well as how extreme beliefs infiltrate every aspect of life. This film is necessary in an age where everybody— conservative/liberal/otherwise— wants to place whole blame for extremism on the doorstep of religion, Islam in specific since 9/11. All such a one-track perspective of the world’s issues achieves is destruction of the individual, alongside that of the collective.

The world is burning. It isn’t only the religious institutions, or law enforcement, or the natural world— it’s all burning. The sooner we accept it, the sooner we might begin to fix it. Or maybe it’s all too late, and the only comfort now is not in religion but in each other and ourselves. Schrader doesn’t claim to have the answers. He’s trying to help us ask the right questions.

Pingback: Reviews: First Reformed (2018) – Online Film Critics Society