The Quarry. 2020.

Directed by Scott Teems. Screenplay by Teems & Andrew Brotzman.

Starring Shea Whigham, Bruno Bichir, Michael Shannon, Catalina Sandino Moreno, Alvaro Martinez, Abel Becerra, Jimmy Gonzales, Bobby Soto, & Rose Bianco.

Metalwork Pictures / Prowess Pictures / Rockill Studios

Rated R / 98 minutes

Crime / Mystery / Thriller

★★★

DISCLAIMER: The following essay contains spoilers

Scott Teems has proved himself well enough with his TV work on both Rectify and Narcos: Mexico as both writer and director. He also wrote and directed a fantastic 2009 film starring the incomparable Hal Holbrook, That Evening Sun. His next big move in the world of film is as one of the writers of the upcoming sequel Halloween Kills. Before that, Teems has offered up his first feature film in 11 years, The Quarry. Although it’s not as great as his other work, mostly a lukewarm crime-thriller with existential vibes, it has a lot of potential buried in its screenplay.

Scott Teems has proved himself well enough with his TV work on both Rectify and Narcos: Mexico as both writer and director. He also wrote and directed a fantastic 2009 film starring the incomparable Hal Holbrook, That Evening Sun. His next big move in the world of film is as one of the writers of the upcoming sequel Halloween Kills. Before that, Teems has offered up his first feature film in 11 years, The Quarry. Although it’s not as great as his other work, mostly a lukewarm crime-thriller with existential vibes, it has a lot of potential buried in its screenplay.

The story follows a drifter (Shea Whigham) on the run, whose situation becomes even more dire than it was already after he murders a preacher named David Martin (Bruno Bichir). He covers up the crime, then takes on the preacher’s identity before going to a small town near the border where Martin was headed. There, he meets Celia (Catalina Sandino Moreno) and her lover, the local lawman, Chief Moore (Michael Shannon). He begins to preach the word of God to his new flock. Except his identity slowly begins to come under suspicion after Chief Moore arrests a young Mexican man for the crime the drifter committed himself.

The Quarry never quite finds it footing, despite the fact Whigham, Moreno, and Shannon each offer loads of heart in their respective performances. There are dark, exciting elements in Teems and Andrew Brotzman’s screenplay, they simply don’t fully make it onto the screen. Their modern morality tale touches on major themes present in Teems’s other work, specifically Rectify and That Evening Sun: guilt, redemption, and the harsh fact that the law doesn’t always serve those who need it on their side most. What The Quarry brings in addition to all that is adding race and religion into the mix. And for whatever the film lacks, it’s a timely piece of fiction that brings together issues of immigration and whiteness in a day and age when Making America Great is nothing more than a racial smokescreen hiding the thinly veiled racism of White America.

“People will say anything to save themselves”

There’s a strong parallel built up throughout the film between the drifter, posing as preacher, and the lawman, Chief Moore. On the one hand, the drifter’s clearly crossed the moral line via murder. On the other hand, Moore displays highly questionable morality as an officer of the law because he’s compromised by barely hidden racism. Moore only suspects the drifter once it’s far too late. His willingness to believe a white man he’s known for only a few days over people of colour is extremely telling. They’re both operating under a sense of fake identity: the drifter wholly takes on a new persona, Chief Moore lives a lie as a discriminatory wielder of the law. Police officers are revered by so many, especially white Americans— though in Canada we’re no stranger to the sentiment, either. When white supremacists have long ago deeply infiltrated every aspect of U.S. life (a couple good articles here + here), embedded in the country’s very institutions, Moore stands as a prime example of how a badge doesn’t automatically make someone a good, moral person. In fact, the badge only amplifies who a person was already, suggesting Moore’s ideas about Mexicans and criminality were ingrained in him long before he ever joined the force. No coincidence Moore’s father was a cop, too.

There’s a strong parallel built up throughout the film between the drifter, posing as preacher, and the lawman, Chief Moore. On the one hand, the drifter’s clearly crossed the moral line via murder. On the other hand, Moore displays highly questionable morality as an officer of the law because he’s compromised by barely hidden racism. Moore only suspects the drifter once it’s far too late. His willingness to believe a white man he’s known for only a few days over people of colour is extremely telling. They’re both operating under a sense of fake identity: the drifter wholly takes on a new persona, Chief Moore lives a lie as a discriminatory wielder of the law. Police officers are revered by so many, especially white Americans— though in Canada we’re no stranger to the sentiment, either. When white supremacists have long ago deeply infiltrated every aspect of U.S. life (a couple good articles here + here), embedded in the country’s very institutions, Moore stands as a prime example of how a badge doesn’t automatically make someone a good, moral person. In fact, the badge only amplifies who a person was already, suggesting Moore’s ideas about Mexicans and criminality were ingrained in him long before he ever joined the force. No coincidence Moore’s father was a cop, too.

Just as Shannon’s character calls the law, and those meant to uphold it, into question, Whigham’s drifter taking on the identity of a preacher likewise forces us to ask questions about religious faith. The drifter himself recognises the preacher’s role in organised religion as incidental. “It‘s not me you‘re here for,” he tells his new congregation, “I just say the words.” Yet the people who’ve come to hear him talk, all of them Mexican, see something in him. They don’t realise he speaks so eloquently about guilt, aided by the Bible, because he knows guilt intimately— he killed before even murdering the preacher. His presence as fake preacher allows us to look at the hypocritical nature of certain religious concepts, namely the idea of forgiveness. Moore tells the drifter: “Forgiveness only works in a world where people learn their lessons.” The automatic, seemingly unconditional forgiveness of God— doubly so for the Catholics, which I know all too well— is a farce, and the drifter’s prime example, having not learned his lesson after killing the first time, repeating his lethal mistakes.

There are a few ways the racism in Chief Moore comes out. Moore represents an inability to see past race. When he and the pretend preacher are talking about Mexican immigrants the latter remarks how they’re “all minorities” nowadays in that part of the country, referring to the working class town. Moore replies: “Last time I checked I was white.” He’s completely incapable of recognising anything but race, not seeing class, only colour. It only gets worse from there, as Moore espouses views of race and criminality that have a long, ugly history. He sees Mexicans as criminals, often offending Celia by saying nasty racial things. He refers to criminals in town, whom he views as immigrants, as “bugs” coming out at night, or “mud” that needs sweeping “off the streets.” He sees criminals as brown, and considers criminals dirt or an infestation— the Great Orange Hype often refers to immigrants as having ‘infested America,’ or that time he called Baltimore rat and rodent infested, and it’s an age old page out of the racist/xenophobic playbook that Hitler also used against the Jews (just one historical example of many). Again, quite a timely story, shown through use of language referring to dirt/infestation in the film’s screenplay.

There are a few ways the racism in Chief Moore comes out. Moore represents an inability to see past race. When he and the pretend preacher are talking about Mexican immigrants the latter remarks how they’re “all minorities” nowadays in that part of the country, referring to the working class town. Moore replies: “Last time I checked I was white.” He’s completely incapable of recognising anything but race, not seeing class, only colour. It only gets worse from there, as Moore espouses views of race and criminality that have a long, ugly history. He sees Mexicans as criminals, often offending Celia by saying nasty racial things. He refers to criminals in town, whom he views as immigrants, as “bugs” coming out at night, or “mud” that needs sweeping “off the streets.” He sees criminals as brown, and considers criminals dirt or an infestation— the Great Orange Hype often refers to immigrants as having ‘infested America,’ or that time he called Baltimore rat and rodent infested, and it’s an age old page out of the racist/xenophobic playbook that Hitler also used against the Jews (just one historical example of many). Again, quite a timely story, shown through use of language referring to dirt/infestation in the film’s screenplay.

While Moore’s symbolic of a barely concealed racism, specifically in American institutions like the justice system, the drifter represents an even more common, prevalent racism built structurally into America. When the drifter kills the preacher he literally erases the life of a person of colour by assuming the man’s identity, effectively treating Mexicans as replaceable objects in a white economy. More than that, the drifter uses the quarry— an open-pit mine, a space of capitalist production— to conceal his crime. He makes the preacher part of the quarry, like the stone being mined.

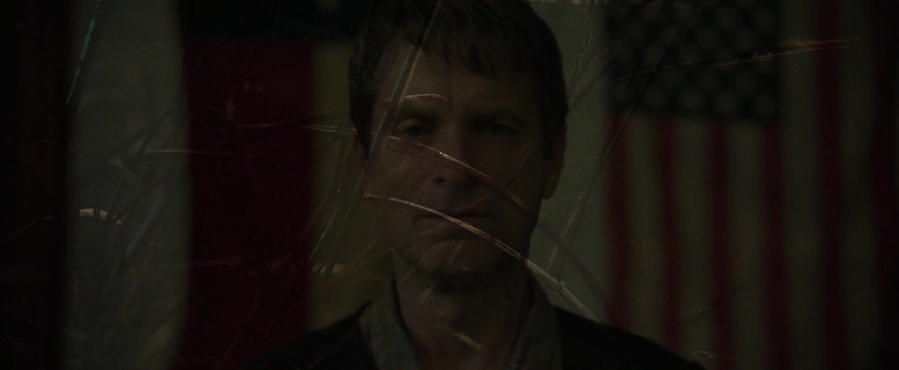

The drifter’s crime becomes an allegory for how POC are used up by America as a form of natural resource in a capitalist system— same as how politicians treat immigrants, legal or otherwise, as labour power, just another resource to consume. It’s colonial opposition to Kantian ethics: people of colour, to White America, are nothing more than a means to an end instead of ends unto themselves. The most evident moment of this is after the drifter’s framed another man— a young Mexican— for his brutal crime, and the guy escapes, getting grazed by one of Moore’s bullets before leaving a trail of blood behind him. The following shot of blood dripping off blades of grass fades into one of the drifter, his face filled with guilt, standing in front of an American flag in the makeshift courtroom. A powerful, devastating image of a white American standing by as he destroys not one but two people of colour, letting the system consume them while the power of the nation and its justice system do nothing to stop it.

“Forgiveness only works in a world where people learn their lessons”

Teems’s The Quarry never gets cooking with gas and, at times, the whole premise feels like a wasted exercise. Whigham’s great, as always, but I can help feel it’s a shame a starring vehicle for him didn’t offer more. Shannon and Moreno each do good work, though Shannon is relatively subdued and his talent feels underused. The story and its plot(s) are good, they just never take off, which can make 98 minutes feel longer than intended. Doesn’t mean there aren’t interesting things to take away.

Teems’s The Quarry never gets cooking with gas and, at times, the whole premise feels like a wasted exercise. Whigham’s great, as always, but I can help feel it’s a shame a starring vehicle for him didn’t offer more. Shannon and Moreno each do good work, though Shannon is relatively subdued and his talent feels underused. The story and its plot(s) are good, they just never take off, which can make 98 minutes feel longer than intended. Doesn’t mean there aren’t interesting things to take away.

Teems does a fine job with the major themes he carries across a lot of his work so far, and hopefully whatever project he takes on as director next will bring more growth. The Quarry, in spite of what holds it back, makes a strong attempt to interrogate issues of whiteness and morality. Now more than ever we need these types of stories being told on a larger scale. We need white filmmakers and writers to stop trying to tell the stories of other cultures and races (I’m looking at you, Wind River!). White artists dying to tell stories about race should focus on issues we face as white people— rather, the issues caused by whiteness that have ramifications from the economic, to the social, to the political.

Pingback: From Our Members’ Desks (May 11, 2020) | Online Film Critics Society