Burning. 2018. Directed by Lee Chang-dong. Screenplay by Chang-dong & Oh Jung-mi.

Starring Yoo Ah-in, Steven Yeun, & Jeon Jong-seo.

Pinehouse Film/Now Film/NHK

Not Rated. 148 minutes.

Drama/Mystery

★★★★★

Disclaimer: The following article contains heavy spoilers!

Lee Chang-dong’s Burning absolutely will not appeal to everyone. The film’s near two and a half hours long and not dialogue heavy. Much of what the story offers is gleaned from the quiet, subtle scenes rather than its brief thriller-like moments. Best to know going in this is an experience that requires work to piece things together on the viewer’s part, if that’s actually possible in a finite sense.

Lee Chang-dong’s Burning absolutely will not appeal to everyone. The film’s near two and a half hours long and not dialogue heavy. Much of what the story offers is gleaned from the quiet, subtle scenes rather than its brief thriller-like moments. Best to know going in this is an experience that requires work to piece things together on the viewer’s part, if that’s actually possible in a finite sense.

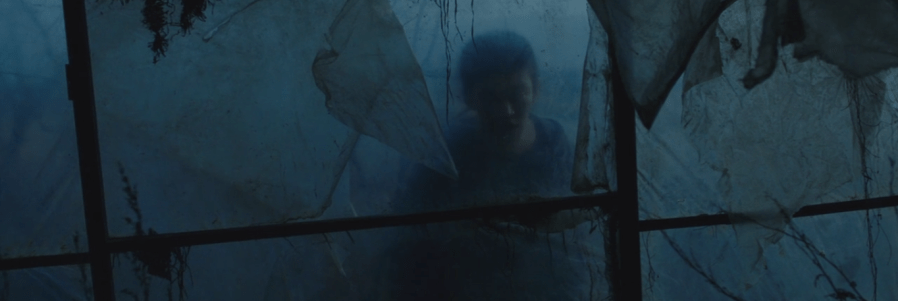

The screenplay by director Lee and co-writer Oh Jung-mi is adapted loosely from the short story “Barn Burning” by Haruki Murakami, from his 1993 collection The Elephant Vanishes. The story centres on South Korean millennial loner, Lee Jong-su (Yoo Ah-in). He has a random encounter with Shin Hae-mi (Jeon Jong-seo), a young woman who was his neighbour during childhood. They spend time together and have sex. When Hae-mi goes on a trip to Africa she asks Jong-su to look after her cat. When she returns she’s with the charming, bourgeois Ben (Steven Yeun), and Jong-su becomes third wheel. One night, Ben tells Jong-su about his pastime: burning down derelict greenhouses. He says he’ll burn another soon. And suddenly, Hae-mi goes missing. Or, does she?

Viewers who crave resolution won’t find it here. Then again, maybe they will. This is a poetic riff on the original story by Murakami, which takes a much different path. In straying from the source material in important ways, Burning becomes a postmodern mystery about fleeting relationships in the 21st century, as well as illustrates how alienated young people have become from themselves and the people around them in the urban landscape, often through no fault of their own.

Urbanism is an obvious theme. Lee hones in on a division between the rural and the urban, in terms of physical location – socially and economically – and also in terms of class division. We’re able to see how the city scatters people due to class, geographically and psychologically. Jong-su has to go back to his father’s farm on a rural stretch of land, whereas Hae-mi lives in the midst of a crowded city in one of those typical South Korean apartments with an electronic keypad outside for entry. She does stuff like pantomime and take acting classes. He has to look after dad’s farm— speaking of dad, he’s got emotional issues, so much so he’s in court up on charges for his violent temper. Their worlds exist so far apart, yet they grew up in the same area.

Urbanism is an obvious theme. Lee hones in on a division between the rural and the urban, in terms of physical location – socially and economically – and also in terms of class division. We’re able to see how the city scatters people due to class, geographically and psychologically. Jong-su has to go back to his father’s farm on a rural stretch of land, whereas Hae-mi lives in the midst of a crowded city in one of those typical South Korean apartments with an electronic keypad outside for entry. She does stuff like pantomime and take acting classes. He has to look after dad’s farm— speaking of dad, he’s got emotional issues, so much so he’s in court up on charges for his violent temper. Their worlds exist so far apart, yet they grew up in the same area.

A major distinction between class comes from the concepts of “Little Hunger” v. “Great Hunger” mentioned by Hae-mi when she speaks about the Kalahari Bushmen, indigenous people in Southern Africa. These two concepts of hunger are about a search for meaning, which Carl Jung wrote about, too. Little Hunger corresponds to literal hunger of the body, and Great Hunger is the larger search to find meaning in life. This dichotomy of hungers directly speaks to class, and class itself is embodied by the character of Ben.

“He’s like a protagonist in a story”

The theme of class is illustrated best comparing Ben with Jong-su. Jong-su, as a budding writer, has an affinity for American literature from the first half of the 20th century, from his favourite William Faulkner – also Father Gore’s favourite author – to F. Scott Fitzgerald. He refers to Ben as “the Great Gatsby” which holds a ton of thematic weight re: money/class, as well as the fact Ben’s a mysterious character not unlike Jay Gatsby. No coincidence there’s a scene with Trump on TV, coupled with Gatsby – considering some of the Donald’s financial ties are unknown – because Jong-su discovers money’s the only thing that matters, whether it affords you a higher class of restaurant or the mobility to pick up and move on to a new city whenever you want.

Jong-su’s existence is determined by economics. He lives on his dad’s farm when we meet him. The farm sits on land right on the border of the DMZ, where South Korea meets North Korea. All day Jong-su hears the constant drone of the DPRK broadcast through speakers like a perpetual reminder of his socioeconomic location, pointing out the geography of class. Then there’s Ben in his bourgeois loft, eating and drinking tea in fancy restaurants. One scene shows an unambiguous class division between these characters: Jong-su is down on the street eating junk and street food from a foil wrapper while Ben’s across the street, storeys up, running on a treadmill in an upper class gym.

Pantomime, courtesy of Hae-mi, is better than a plot point for Jong-su to chase. Pantomime involves imagination, imagination is freedom, and freedom isn’t available to everybody. Jong-su doesn’t have the freedom to go to Africa even like Hae-mi does, neither does he have even a quarter of Ben’s freedom with his mysterious source of income. She essentially brings Descartes into the equation suggesting it’s only a matter of thinking and believing to make something a reality— sort of an “Cogito, ergo sum” statement. This comes crashing down around her as false in a scene when the three of them get high together one night at Jong-su’s place. She dances topless to jazz in the wind, culminating in tears. Her naked body’s free while she’s there in that place she once escaped for the city, just like she’s caught between Jong-su and Ben as two living, breathing symbols of rural/urban. Class determines freedom, more than ever in a modern/postmodern world, so in the place from which Hae-mi came she feels this hard truth’s pull. Class is only one aspect of Burning. Lee’s film involves people around the (older) millennial age, and the director himself has talked about the millennial experience reflected in the story’s mystery. The reason class is so prevalent is because for millennials it’s become more of an issue than it was for our parents, who for a while were able to at least hang onto a middle class, which has all but vanished now with rapidly growing income equality in the 21st century. While Jong-su’s father had the farm, Jong-su himself is left with no job simply because he’s living on the farm, disconnected from the city. He walks out of a job interview because he knows he won’t get it due to living so far from where he’d work. This is a near Kafkaesque spiral into alienated existence, only made worse by the mystery Jong-su experiences later.

Class is only one aspect of Burning. Lee’s film involves people around the (older) millennial age, and the director himself has talked about the millennial experience reflected in the story’s mystery. The reason class is so prevalent is because for millennials it’s become more of an issue than it was for our parents, who for a while were able to at least hang onto a middle class, which has all but vanished now with rapidly growing income equality in the 21st century. While Jong-su’s father had the farm, Jong-su himself is left with no job simply because he’s living on the farm, disconnected from the city. He walks out of a job interview because he knows he won’t get it due to living so far from where he’d work. This is a near Kafkaesque spiral into alienated existence, only made worse by the mystery Jong-su experiences later.

After Hae-mi goes missing it consumes Jong-su attempting to figure out where she’s gone. He comes to believe Ben is behind it. His authorial mind leads him to believe everything’s connected. Early on, after Ben discovers Jong-su wants to be a writer, he’s asked by Hae-mi: “What‘s a metaphor?” He suggests to ask Ben. This plants the seed for later when Ben tells Jong-su about his sneaky pastime of burning old greenhouses. The hopeful writer takes this as metaphor, convincing himself the affluent gentleman could possibly be a serial killer once Hae-mi vanishes. This is never confirmed. Lee and his co-writer never spell out in certain terms whether Ben is or is not actually a killer. Every suggestion’s there – maybe – just no definitive proof.

And so the question becomes, what happened to Hae-mi?

Ben could’ve killed her. He’s a man shrouded in mystery with a bathroom drawer full of women’s jewellery and a case of makeup he uses on his various flings. At the same time we can’t count out Hae-mi’s agency. Her own family see her as a liar and unreliable, owing her money before she ran away to the city, so she could be the type to pick up and take off at any time convenient to her, particularly if she was in debt or some kind of money trouble. She went to Africa on a trip, meaning she’s got a passport. Not out of the realm of possibility she was sick of the city, or of Jong-su, or Ben, or all of it. Jong-su doesn’t want to believe Hae-mi would leave and not tell him, which is either romantic or presumptuous. The viewer’s left to decide for themselves what exactly they believe is true. We do see what Jong-su believes in a grim and shocking finale. We’re nevertheless left with ambiguity for ourselves, epitomising the mystery of postmodern urban life many millennials know today as just another part of our existential confusion.

“To me, the world is a mystery.”

Is Jong-su obsessed with Hae-mi to a toxic point? Was Hae-mi exercising her freedom and running off to live her life somewhere without worrying about what any man back home’s thinking? Could Ben be a killer of women, working his way through the city and playing sick games with any man who dares enter his path? Burning is filled with simmering mystery that’s never fully resolved. If, as a viewer, you need a concrete ending this will not scratch the itch. It’s a film worth experiencing if you like the medium to challenge your powers of perception.

Is Jong-su obsessed with Hae-mi to a toxic point? Was Hae-mi exercising her freedom and running off to live her life somewhere without worrying about what any man back home’s thinking? Could Ben be a killer of women, working his way through the city and playing sick games with any man who dares enter his path? Burning is filled with simmering mystery that’s never fully resolved. If, as a viewer, you need a concrete ending this will not scratch the itch. It’s a film worth experiencing if you like the medium to challenge your powers of perception.

Lee’s film, like the greatest literature and cinema, can mean different things to different viewers. Father Gore chooses to see the story as an allegory about the alienated world in which we live today, especially for people 35 and under, whether we’re alienated from ourselves/each other by class, by gender, by geography, or any other number of aspects to life. The 21st century is increasingly a world where nothing’s certain, in which nothing and no one makes much sense, and the answers are never easily identifiable. Steven Yeun’s performance as Ben seems symbolic of this ambiguity— never fully letting us in to see who Ben is beneath the exterior, never allowing us to understand the character enough to know him wholly, but always keeping him compelling and driving the story’s sense of mystery.

Burning, as a whole, reflects the misery and mystery young people experience this day and age as they struggle to find meaning in their often mundane everyday lives. Is there meaning? Or, do we fabricate it out of thin air, for better or worse, like Jong-su might have done? The film, like life, is subjective, and the answers, if any, are in your hands. The choices, and the mistakes, are (y)ours to make.

Pingback: Via Father Son Holy Gore-The Existential Miseries & Mysteries of Class in BURNING – Fang & Saucer

Pingback: From Our Members’ Desks (Dec. 17, 2018) – Online Film Critics Society